On January 23rd, all of the humanitarian demining NGOs working in Colombia met in an upscale hotel in northern Bogotá to review their work plan for 2020. Since early that morning, Angela Orrego had received several Whatsapp messages from an official of the Colombian government’s Office of the High Commissioner for Peace, reminding her of the meeting and the hotel’s location. But when Orrego and two of her colleagues from Humanicemos, one of those organizations created to destroy landmines, arrived, another government official barred them from entering.

“I’m very sorry,” she told them. The meeting was partially funded by the U.S. State Department, she explained, and that meant they could not participate. The reason was that Orrego is a former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) combatant who left her weapons three years ago as part of the Colombian peace deal and who leads the demining organization created in 2018 by a hundred former guerrillas as a reincorporation project into civilian life. The problem is that U.S. law prohibits any resources from that country benefiting members of organisations on its government’s list of terrorist organisations. The former FARC have not yet been removed despite having signed a peace accord in late 2016 and laid down their weapons in mid-2017.

Beyond this legal complexity, that the national planning event on demining organized by the Colombian government was being paid by the Americans is something that officials had to know long before that morning. In fact, it was not the first time this happened. Last year, at another sector-wide meeting inside the Foreign Ministry, members of Humanicemos were denied snacks and use of translation equipment, since both were paid for with U.S. funds.

These impasses underscore the bureaucratic hurdles created by President Iván Duque’s government and hindering Humanicemos from beginning to destroy landmines, according to six persons who work on the issue. This has meant that one of the most tangible and powerful ways in which former FARC guerrillas can repair the damage they caused to thousands of victims of the conflict has floundered so far.

The dream of Humanicemos

Humanicemos, devised as a project for the social and economic reincorporation of former guerrillas, is a direct heir of the Havana peace talks. Its origin goes back to the two pilot projects of humanitarian demining carried out by the Santos government (2010-2018) and the FARC in 2015, in the midst of negotiations, to de-escalate conflict and build trust between the two. For over a year, an improbable team worked together in the rural hamlets of El Orejón in Briceño (Antioquia) and Santa Helena in Mesetas (Meta). Guerrillas provided information on landmine location and workings, the Norwegian People's Aid (NPA) carried out vital non-technical field studies and, finally, soldiers from the Colombian Army's Demining Battalion dismantled them. In total, together they cleared 39,215 square metres and destroyed 70 improvised explosive devices.

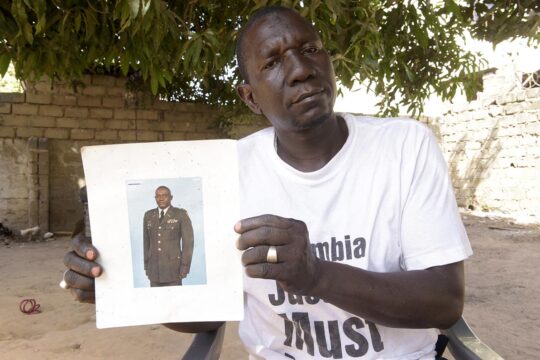

Many of Humanicemos’ staff worked on those pilots. Director Angela Orrego led the group of guerrilla explosives experts in El Orejón, while technical field manager Germán Balanta did the same in Santa Helena. “If there's one thing that has given me satisfaction in life it's that effort, because we all put our boots on. The Government realised that we could work as a team and that peace is our will. The result of these pilots led us to think: if demining involving former combatants has been so successful, why not create our own organization?” says Orrego, who spent three years in the guerrilla communications team in Havana before going to Orejón.

The country still ranks second in the world in landmine victims after Afghanistan.

That was the embryo for Humanicemos, a civilian demining organization almost entirely comprising former combatants. More than 90 per cent of its 113 employees today are former FARC members in transit to civilian life, as are all nine of its board members and 51 assembly members. Their dream is to join the other seven civilian organizations currently clearing landmines in a country which still ranks second in the world in landmine victims after Afghanistan. When they started organizing in 2018, expectations ran high. According to Orrego, they even compiled a database with 500 former guerrillas interested in jobs destroying landmines, many of which had been installed by FARC itself. Enthusiasm was also felt on the other side. Rafael Pardo, then President Juan Manuel Santos' post-conflict minister, announced that Humanicemos would hire 1200 ex-guerrillas, a promise that many in the sector found overly optimistic at a time when the largest civilian organisation – British Halo Trust – had 300 employees.

Risking U.S. funding

By March 2018, former FARC guerrillas began training in landmine clearance. Humanicemos staff was trained by other civilian organizations on how to carry out non-technical surveys to establish perimeters, how to destroy mines, and how to educate local communities on mine risk. Halo Trust trained 40 of them, NPA 28, the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines 20 and UNMAS – the UN's mine action arm – 40 more. They did this with $4 million dollars pledged by the Norwegian government and UN Secretary-General António Guterres’s Peacebuilding Fund (PBP).

In addition to its 90 deminers, Humanicemos is also considering employing other former combatants with knowledge of landmines under a figure it dubbed ‘local guides,’ to work hand-in-hand with explosives experts in locating and destroying them. Their idea is not only to hire them directly but to lend them to other organizations working in Colombia, such as NPA, Halo Trust, France’s Handicap International, Denmark’s DDG, Italy’s Perigeo or locally-based CCCM and Atexx. Their information is key to establishing more accurate perimeters and accelerating clearance, saving time and money.

Around May 2018, the biggest problem emerged. The Organization of American States (OAS), which has traditionally performed the mandatory technical evaluations of deminers in Colombia and had been part of the project from the beginning, announced that it had to withdraw because of U.S. funding, which – they argued – prevented them from working with former FARC combatants. Their announcement had a ripple effect. British NGO Halo Trust decided, to avoid risking U.S. funding in the future, that it too could not continue training members of Humanicemos. Half of its trainees had to be taken up by CCCM and UNMAS.

This legal and political reality meant that the Colombian government had to find another third party to certify former combatants’ demining skills. Descontamina Colombia, the agency then in charge of demining and later absorbed by the High Commissioner for Peace, tried to think of a creative transitory solution, but the end of the Santos government arrived without one. During the transition between the Santos and Duque administrations in 2018 it was clear an alternative solution to the problem was needed. Almost two years later, it remains unresolved.

Although the start for Humanicemos was slow under President Santos, difficulties increased upon Duque’s arrival.

The government’s shifting organization

Although the start for Humanicemos was slow under President Santos, difficulties increased upon Duque’s arrival. Three officials from the international community and two from the demining sector, granted anonymity so they could discuss the issue more candidly, feel that the current government has dragged its feet on approval of Humanicemos.

Since late 2018, Duque’s government had decided that UNMAS should be in charge of external monitoring of their deminers, as it does in many other mine-affected countries. On December 6th, Emilo José Archila – Duque's stabilisation advisor who had demining under his wing at the time – approved that UN agency due to its “recognised international technical capacity”, an official document seen by Justice Info stated. “Everything should have been resolved then,” says a foreign diplomat.

However, it wasn’t. Two months later, Duque reshuffled post-conflict tasks and handed over the mine action programme to peace commissioner Miguel Ceballos. His office absorbed the demining agency. Permits sought by Humanicemos, including the selection of UNMAS as an independent verifier, fell into limbo.

Last August, the demining decision board – where the Ministry of Defence, the Military Forces’ General Inspectorate and the peace commissioner sit – finally approved renewal of Humanicemos' annual accreditation as a demining organization. Then, on 7 November, that same demining decision board finally approved that UNMAS technically verify its deminers. (It did so after the peace commissioner’s office had proposed a public tender that would also include a Croatian NGO called Cromac, with no previous work nor employees in the country. In the end, the UN agency’s greater capacity prevailed.)

Delayed notifications and cancelled mandates

It seemed things were finally solved. But the various institutions that needed the official notification of the different decisions were still waiting for it weeks or months later. After pressure from many in the sector, Ceballos' letter arrived at UNMAS on November 29. But the letter of approval to Humanicemos or – more importantly – to its European Union funders, who could not disburse the money for the project’s second phase without the government’s official approval, was not delivered before December. That notification finally reached the EU mission on December 2nd and allayed anguish at Humanicemos, which three weeks before the end of the year could not pay its employee or office rent. Humanicemos finally received its accreditation renewal letter on December 20, four months after approval, but has not yet gotten the letter selecting UNMAS.

In any case, accreditation of their deminers is still uncertain. The Foreign Ministry – which traditionally has been reluctant to involve the United Nations in the country – decided against signing a new mandate with UNMAS. It was then decided that another UN agency, the UNDP, would serve as their guarantor. That agreement has not yet been signed though.

These decisions will prevent other NGOs from hiring ex-combatants and diminishes the potential of demining for reincorporation and redress of victims.

At least two conditions announced by the peace commissioner’s office in recent months show life will continue to be difficult for Humanicemos: UNMAS was not authorized to certify former guerrillas trained by Halo Trust, NPA and CCCM, who will have to be trained again from scratch, and – in a new decision this year – it will no longer be possible for former guerrillas to work as guides with other civilian organisations. The reasons for these decisions are not clear but, in practice, will prevent other NGOs from hiring ex-combatants and diminishes the potential of demining for reincorporation and redress of victims.

Lost opportunities

“How can we keep people from losing motivation in the face of obvious unwillingness? We've been training for almost two years,” says Angela Orrego. Her spartan office has a map showing the first three areas in the department of Caquetá assigned to Humanicemos for landmine clearance by the previous government. As they wait, they’re working on mine risk education with rural communities, but their sights are still set on clearing landmines and handing over mine-free areas to them.

In these delays, they already lost many former FARC members who were excited about the prospects of demining.

In these delays, they already lost many former FARC members who were excited about the prospects of demining. Most have turned to other projects in the absence of news of their accreditations, although it is difficult to rule out that some might have joined dissident groups who abandoned the peace deal and re-armed.

At least one of Humanicemos’ ideas is more difficult to materialise today, given the dispersal of persons who demobilised. They wanted to organise a summit of former guerrilla explosives experts, which would allow them to document installation patterns and map changing practices across regions, such as where did they use trees, open fields, hillsides or abandoned buildings. “After three years it's a tough task. It was important not to lose the memory of those who know where there are minefields,” says a person working for a demining NGO, for whom the members of FARC’s top brass erred by not compiling data on who these explosives experts were in each guerrilla bloc. “Back then, there was a real possibility that many who are now gone would have come here. It's a pity this opportunity was lost,” adds Orrego.

The government’s lack of urgency

The international community has also been monitoring the situation with frustration. “There is no urgency. How can they send a letter on the 29th of a decision they made on the 7th?” asks an international aid official. Especially when that letter, which Justice Info saw, highlights that “the results of all aspects (...) were positive”. “Let’s say we thought and hoped a decision would be made months earlier,” adds another diplomat, who believes – like the other sources – that this lack of urgency shows the Colombian government doesn’t see it as a security risk.

This lack of urgency shows the Colombian government doesn’t see it as a security risk.

Staff at Humanicemos believes that Duque’s administration has slowed down approval out of fear that the political party created by the former guerrilla will use mine clearance politically. “The government believes that we want to do politics with demining efforts. We have demonstrated over and over that this is not the case, that we understand this is humanitarian work,” says Orrego, explaining that this was precisely the reason why they decided the organization would have to function independently to the FARC party. Peace commissioner Miguel Ceballos and mine action director Martha Hurtado did not respond to questions on the delays faced by Humanicemos.

Demining as redress

In Colombia landmines have left 11,655 direct victims (not counting relatives) and 2018 saw accidents increase for the first time in six years. Much of this responsibility lies with FARC, which were described as “probably the most prolific user of antipersonnel mines among rebel groups anywhere in the world” by the Landmine Monitor report of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines. “The importance of clearing landmines is putting a stop to casualties. As long as there are new victims, people will see their own pain reflected and not the possibility of reconciliation. It will be more difficult for them to move from negative emotions to positive ones,” says Reinel Barbosa, who founded the first nationwide network of landmine victim associations. For him, demining should be considered a preventive action, not a restorative one.

According to the peace deal, destroying landmines is one of the main ways in which former FARC guerrillas redress victims, an unavoidable condition for them to receive more lenient sanctions in the transitional justice system.

In fact, according to the peace deal, destroying landmines is one of the main ways in which former FARC guerrillas redress victims, an unavoidable condition for them to receive more lenient sanctions in the transitional justice system. It could also become one of the restorative punishments imposed by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) as part of the sanctions regime it is currently outlining. In addition, demining is often a necessary previous step for other vital local development programs such as coca substitution or the national landowner cadastre that Duque has made a priority.

And yet, the delays have had one very significant effect: so far no victims – except those of Briceño and Mesetas – have seen former FARC guerrillas clearing mines. Although Colombia’s 8.9 million victims have very different expectations, reparation is one of their priorities. “Demining is an action with a reparative goal. Humanicemos’s actions are a way to fulfil our commitment with non-recurrence of violence and local peacebuilding,” says Orrego, who spent three decades in the FARC under the nom-de-guerre 'Yira Castro'.

These restorative deeds, however, can only be certified individually, and not collectively. This means that only those directly on the ground clearing mines will be able to ask the JEP’s judges to bear their work in mind. Other former guerrillas who are not part of Humanicemos or didn’t participate in the two original demining pilots will not be able to argue this. This should prevent, for example, former members of FARC’s top brass from trying to use Humanicemos to soften their responsibilities before the transitional justice. As one demining expert says, “judges won’t look at who signs a paper saying so, but who’s actually doing it”.

In the midst of these difficulties, the newly-trained deminers are still waiting to being using their skills. “It is how we pitch in to make peace a reality,” says Orrego. “We knew it was not going to be easy, which is why we persist.”