23 years in prison, more than 25 years of a revolutionary's life, including 8 years supervising the torture and execution of thousands of presumed and mostly imaginary enemies, finally got the better of the strength of Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch. The former Khmer Rouge executioner, sentenced to life imprisonment in 2012, died in a hospital in the Cambodian capital shortly after midnight on September 2 at the age of 77.

For eight years, Duch was a key commander of the Communist Party of Kampuchea's security services, in charge of the arbitrary detention, interrogation, torture and systematic execution of those whom the Party, led by Saloth Sar, alias Pol Pot, randomly considered its enemies. First, from 1971 to 1975, it was camp M-13, when the Cambodian communist guerrillas - the 'Khmer Rouge' (Red Khmer), according to the name given to them by King Sihanouk - were in the maquis. Then it was S-21, an ultra-secret prison set up in the heart of the capital, Phnom Penh, during the period when the Khmer Rouge controlled the country, from April 1975 to January 1979. Four years during which it is estimated that a quarter of the Cambodian population perished through bloody purges, mass executions, forced labor, disease, exhaustion and hunger. Until the Vietnamese army invaded the country and pushed the Khmer Rouge back into the mountains for another twenty years of fighting in the name of a totalitarian ideology.

A Khmer Rouge who killed other Khmer Rouge

It was in 1967 that Duch joined the Communist Party, when it was banned and clandestine but not yet a guerrilla group. In January 1968, he was arrested and sentenced to twenty years in prison for sedition. He was freed two years later, thanks to a coup d'état organized by the reactionary and militarist right, supported by the United States - in short, Duch's enemies. He then immediately joined the armed rebellion. And it was in the company of several other professors of his generation that he became a senior member of the secret police. He reached the peak of his revolutionary career between 1976 and 1978, when S-21 was in full swing and purged thousands of Party cadres. Indeed, it is estimated that 80% of the 12,000 or so prisoners identified at S-21 were Khmer Rouge themselves. The heart of Duch's work was to be a Khmer Rouge killing Khmer Rouge. He received orders directly from the supreme organ of the Party, whose paranoia and infernal, voracious and almost anthropophagous cycle of murders he satisfied and fed. The internal enemy was everywhere. It justified all the failures of the Revolution. And the confessions, often grotesque, extorted through terror and torture by agents trained by Duch, allowed the regime to "prove" the multiple conspiracies of which it claimed or believed itself to be a victim.

After the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979, Duch held himself up in the ranks of an increasingly exhausted revolution, but he clearly no longer played any significant role in it. In short, Duch was a major criminal from 1971 to 1979, neither before nor after. No one would probably know his name today if he had not left the incredible S-21 archives intact. Thousands of photos, documents, interrogation reports, execution lists, dated, annotated, signed by this extremely meticulous, efficient, devoted and obedient "comrade", possessed with the lunatic principles of the dictatorship of the proletariat. For historians, the archives of S-21 - the masterwork of Duch - constituted an essential mine of information on the functioning of one of the most secret regimes in history, in a country that had entirely closed itself off from the world in order to, its rulers claimed, transform the old Khmer kingdom into an agrarian utopia surpassing all other revolutions by its radicalism. A project that was inevitably murderous and inevitably vain.

S-21, symbol and museum of the Pol Pot years

In 1979, the S-21 prison, a symbol of the crimes committed, was converted into the Genocide National Museum. It is here that since the 1990s, millions of tourists have come to find out, sometimes in shorts and flowered shirts, about the "Khmer Rouge death machine," as filmmaker Rithy Panh, author of several major films on S-21 and the crimes under Pol Pot, has called it. Some visitors may still have the uncomfortable privilege of having as a guide and witness one of the last two survivors of the dozen or so prisoners who escaped execution thanks to their useful skills (electrician, mechanic, painter...) and thanks to the Vietnamese invasion. It is also in this place that a memorial was erected for the victims. And it is the photos of those who would be killed that have identified the Pol Pot years in the eyes of the world, "the time of the men in black" as some survivors call it.

The notoriety of the place has caught up with its former director, betrayed by his own archives. Uncovered in 1999 by Nic Dunlop, a young Irish press photographer, Duch, who was working under a false identity for an American charity, immediately acknowledged his role. This made him a unique case among Khmer Rouge executives, inclined to deny atrocities or responsibility.

The birth defect of an international tribunal

Duch was quickly put in prison, and never got out of it. Ten years after his arrest, his trial opened before the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), a court composed of both Cambodians and international lawyers, and created after eight years of negotiations between the Cambodian government - itself led by defrocked former Khmer Rouge - and the United Nations. A court that was flawed from the outset, built on a narrow and ambiguous political compromise, against the backdrop of a weak, corrupt and subservient national judicial system, and that would never emancipate itself from the demands of the all-powerful Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge commander who deserted in 1977 before coming back with the Vietnamese army, for whom only five individuals were to be tried.

Duch was the first of them. He was not one of the leaders of the movement and of the party, but his name was more famous than that of the latter, except for Pol Pot, whom Duch had seen only twice in his life. It had been thirty years since the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime. Pol Pot, Son Sen and Ta Mok were dead and international justice could only afford symbolism.

A remarkable trial

In essence, Duch's trial was easy. He was a very cooperative defendant, who acknowledged most of his responsibilities and the facts against him. The mass of documents found at S-21, already well studied by researchers, made for an implacable indictment. Duch was a guaranteed judicial success.

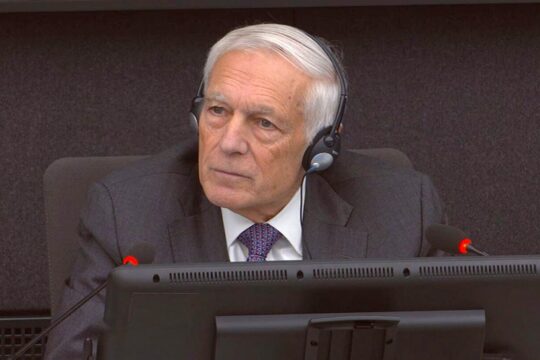

Yet, his trial remains today one of the most remarkable of its kind at the international level. From March to September 2009, almost every day, Duch analyzed and clarified the documents submitted to him, answering questions directly from victims or relatives of victims who, before the ECCC, were involved in the trial as they had never been before any other international court.

Never before had the voice of the executioner been heard in such detail. It was served by an intelligent Duch, endowed with an astounding memory, in turn fighting, coldly clinical or broken by the fright of certain testimonies, repentant or unable to sink to the devastating depths of his memories.

Never had the voice of the victims been so present and opened to stories revealing the extent of the suffering and destruction of families, beyond the killings. This voice was served by witnesses whose evocative power and emotion overwhelmed and destabilized the formal order of the judiciary.

It was a trial with little legal or procedural stakes, which often turned it into a kind of spectacular and heartbreaking truth commission.

How could an exemplary former mathematics teacher from a modest background, loved by his students and concerned about social justice, turned into a ruthless executioner? This question, which is at the heart of the experience of mass crime and often swept away by the technical and fearful logic of trials, had never been so consciously approached as in this case. No one will remember the debates of the second major trial that took place before the ECCC. But literature and filmography on S-21 and the Duch trial is abundant. It seals the historical and judicial memory of the Khmer Rouge crime. And as a result Duch has unwillingly become the symbol of this crime.

When justice expires

In fourteen years of activity, the ECCC has tried only three former Khmer Rouge leaders – Duch first, then in a second trial, Nuon Chea, the regime's number 2, and Khieu Samphan, the former head of state. Two other defendants died before reaching a verdict. Attempts by international prosecutors and judges to prosecute five or six other suspects all failed.

Today, the ECCC appears to be a judicial enterprise at its wits' end, mired in vain, costly and near-absurd proceedings, overwhelmed by the passage of time, disconnected from the interests and priorities of a population born, for 80% of them, after the fall of Pol Pot, and that has resolutely turned its back on a history that has become so remote, covered by the thick layer of ideological dust of another century. Last April, the American NGO Open Society Justice Initiative publicly asked the UN to stop funding the ECCC. This was an unprecedented position for an organization whose support for international criminal justice is unequivocal. Last month, Cambodian judges officially buried one of the pending cases, all of which have been in a deadlock since they were initiated twelve years ago. Duch now dead, only one convict remains alive: Khieu Samphan, 89 years old and still awaiting a final judgment on appeal, thirteen years after his indictment by the ECCC. The passing of the former director of S-21 thus appears to be a vivid anticipation of that of the court that tried him and whose raison d'être has expired.

On 1 September, Cambodians began Pchum ben, a religious festival, the second most important moment of the year. This is the time when, for two weeks, the Khmer people are invited to pray in memory of the dead in the hope of improving their karma. Duch died the following night. As if symbols, right to the end, had chosen him in order to embody History and to go beyond it.