Is it a transitional justice issue? In some cases yes, believes Professor Marc-André Renold, head of the Art Law Centre at the University of Geneva which has been developing the ArThemis project since 2010. This website documents some 150 cases involving restitution of cultural property. Some of the cases are between States, individuals, museums, and some involve local communities. Some date back years, and some are ongoing. The database serves as an open-source resource for restitution issues. In addition, the Art Law Centre has started receiving requests to help mediate in cases, but declined to give details at this early stage.

It took off, Renold recalls, with a landmark case in 2006, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York returned to Italy the Euphronios Krater, a huge urn dating to around 510 BC that had been illicitly excavated in Italy. This case marked, he says, the start in the 2000s of a new trend of restitutions of archaeological objects to Italy by US museums. “So the MET was the first museum to do so, followed by the Boston Museum of Fine Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Getty,” Renold continues. This trend also put pressure on museums elsewhere for restitution of certain artefacts.

Around the same time, his University received a Swiss research grant to develop a database of cases and “understand how disputes are solved with regard to cultural heritage”. Renold sought support from UNESCO because, he says, “UNESCO is the main actor in the field as regards States and restitution of cultural heritage”. That moral support was secured from the beginning, and more recently the project has received UNESCO funding to make the website fully bilingual (English and French).

The database serves as an open-source resource for restitution issues. In addition, the Art Law Centre has started receiving requests to help mediatein cases, which cannot be mentioned at this stage.

“Different, original solutions”

In the beginning, says Renold, his team had no preconceived idea as to what were the preferred methods for solving disputes. “We are lawyers, so we first thought about court cases,” he told Justice Info. “But we wanted to see if there are alternative methods. And that’s how we got involved in setting up the database and finding out that, although going to court is still an option which claimants revert to, there are more and more often other ways of solving these issues such as international arbitration, mediation, conciliation or even simple negotiation,” he says. They were worried at the start that they would not have enough material, “but it turns out we have loads. We now have some 150 case notes and we can go on, because new material is coming all the time”.

Among prominent cases documented on the ArThemis website: repatriation of Tasmanian Aboriginal human remains from the Natural History Museum in London (2007) under a mediation agreement; Herero and Nama skulls returned from Germany to Namibia in 2011 after negotiations between the two States; and the bottom half of a Zimbabwe stone bird, considered sacred by the Shona community, returned on permanent loan from Germany having passed through many hands including the Russian Army during World War II.

Often it took time and diplomatic pressure, and sometimes the threat of court action. Prestigious museums tend to want to avoid being dragged through court, with the damage to their reputation this may entail. “What we’ve noticed first is the diversity of procedures and solutions,” says Renold. “If you go to court the answer will generally be black or white: you win or you lose, you obtain restitution or you don’t. If you use alternative methods, let’s say negotiation or mediation, you might find different, original solutions.”

Human remains

Human remains are particularly sensitive. In the Tasmanian case, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre made several requests from the 1980s to the London Natural History Museum for the return of 17 Aboriginal human remains bought by or donated to the museum after being collected from Tasmanian burial sites in the 19th century. When their dispute was brought to the London High Court, the court’s judge suggested proceeding by mediation.

Each of the parties appointed a mediator. The museum pursued scientific interests, considering data collection and the preservation of genetic material to be fundamental for future research. The Aboriginals wanted the remains to be preserved according to their traditions and did not want “any physical interference with the remains and no future desecrations”. Ultimately, the mediator succeeded in convincing the parties to agree to a compromise. The Aboriginals acknowledged the importance to retain the DNA collected so far and the NHM scientists in turn agreed that the remains and all pertinent documentation should be vested in a Tasmanian medical facility.

Return without an official apology

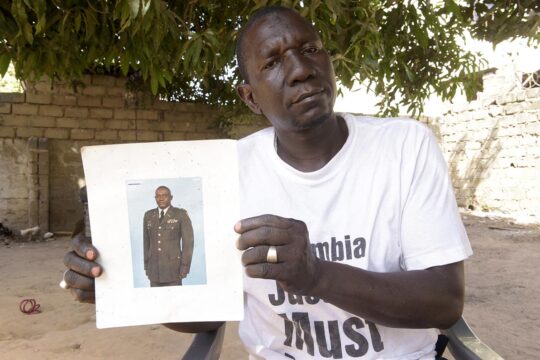

In the Namibian case too, restitution took a long time. After its independence in 1990, Namibia petitioned Germany to return several skulls of deceased members of Herero and Nama communities. The skulls had been brought to Germany after the mass killings committed by German authorities between 1904 and 1908 to quell an uprising against the colonial occupation. At the time of the restitution claim, the skulls were being held at the Charité Universitätsmedizin in Berlin. The Charité and German authorities agreed to conduct the necessary research on the skulls and to return them to Namibia. This was done in September 2011, with an official ceremony held in Namibia on 5 October 2011.

The hospital’s CEO, Karl Max Einhäupl, was quoted as saying that such a return would “express respect and contribute to the honourable remembrance of the victims”. When the remains had been brought to Germany, he recalled, they were not regarded as “human remains but as material with which to investigate and classify race”.

This shift in attitude shows that the Charité’s standards regarding the conservation, research, and exhibition of human remains have considerably changed in the past decades, ArThemis notes on its website. But, it comments, “whether the outcome of this dispute was actually satisfactory for the Namibian indigenous communities remains questionable, especially considering Germany’s reluctance to apologize and formally and expressly take legal responsibility for the genocide. Some critics argue that an effective settlement can only be achieved above any material aspects, in the form of redress and recognition of the caused harm. Adhering to this approach, the Charité stepped in to act in place of what should have been the German Government’s responsibility”.

Right time for action

“The time is right for reflection,” on this issue, says Renold, “because of the present debate on the restitution of items taken during the colonial period. In fact, it is even a time for acting more than reflecting. There’s a political environment in France and then of course Black Lives Matter. Germany is also very involved in reflecting on its colonial past.”

In France, for example, MPs recently voted to return some prized artefacts to Benin and Senegal that were seized during the colonial era and have been displayed in Paris museums. The artefacts include the throne of Benin's King Glele and a sword and scabbard once said to have belonged to Senegal's military and religious figure, Omar Saidou Tall.

An activist from the DR Congo was meanwhile fined €1,000 for removing an African artefact from a Paris museum in protest at France's colonial-era looting of art. Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza grabbed a 19th century Chadian wooden funerary post from the Quai Branly museum in June in a protest that was live-streamed, saying he had "come to claim back the stolen property of Africa", but was stopped at the door. Fining him for aggravated robbery, the judge said he wanted to "discourage" similar stunts. "You have other ways of drawing the attention of politicians and the public" to the issue of colonial cultural theft, he said.

And much remains to be done. Renold hopes that ArThemis can serve as a resource particularly for developing countries wanting to claim cultural property back. African states, he says, are increasingly claiming the restitution of artefacts looted during colonial times, but “they might go to press, perhaps contact a Ministry in a European State saying they claim the restitution of a particular item, but often nothing follows”. They need added expertise, he thinks.