JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

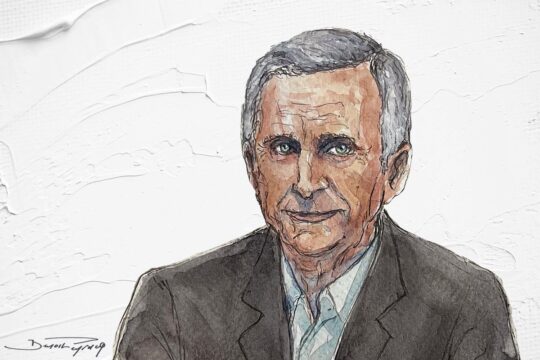

Aaron Weah

Civil society activist and scholar on transitional justice issues

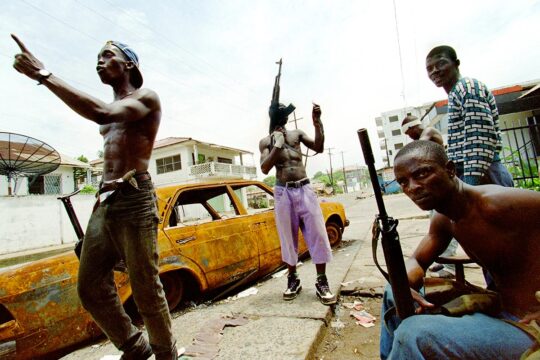

Aaron Weah is a leading expert on transitional justice in Liberia. He is the only Liberian scholar to have attended the hearings in the war crimes trial of Gibril Massaquoi before a Finnish court that relocated to Liberia between February 15 and April 7. Before the trial resumes in neighbouring Sierra Leone, he shares his reflections on how Liberians have mostly been forgotten in this justice experiment but how it may still reinforce their desire for accountability.

PART 1: The Massaquoi trial

JUSTICE INFO: Early this year, a Finnish court announced that it would hold a major part of the trial of Gibril Massaquoi – a former Sierra Leonean rebel commander residing in Finland and accused of crimes committed in Liberia – in Monrovia, Liberia’s capital city. This made the Massaquoi case the first war crimes trial to be held on Liberian soil. What were the expectations in Liberia before the Finnish court came in mid-February?

AARON WEAH: It sounded exciting and too good to be true. Unlike his predecessor Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was identified by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for her alleged role in the conflict, Liberia’s president George Weah is uncontroversial on this issue. He is also on record for calling for the establishment of a war crimes court as far back as 2004. But there is a twist here: Weah’s 2017 election happened as the result of a compromise with people like Prince Johnson [a former warlord from Liberia’s first civil war] and other actors involved in the conflict. It has become something of a strategy now for anyone aspiring to be president to forge an alliance with former heads of warring factions who have entrenched themselves in their ethnic communities and counties and are interpreting the war for a majority of Liberians who do not have an independent opinion on what it was about. Because today 60 to 65% of the population were born during the war or after the 2003 Accra peace agreement, you have a big chunk of the Liberian population that are basically being told by politicians what they think the war was about. That’s why it was difficult to really believe that a war crimes court was coming to Liberia in the midst of all these complications. But once the information proved to be true, I thought that the government was inclined to a new deal of addressing atrocities in Liberia. The civil society was excited that something similar to the TRC public hearings – where you could go and sit as long as you wanted – was happening.

So you can imagine the confusion and frustration in the civil society when it appeared that not only the trial was not available to villagers, residents who have suffered the atrocities, but that it hasn’t even allowed some very important activists to participate. It was all shrouded in confidentiality; access was very restricted and very limited. In fact the debate about the Finnish trial will happen after the verdict, when people really get to know that there was a trial here, that it has been happening right in our faces and yet we were not allowed to go there. What was the value of the whole thing when critical sectors such as civil society and victims’ groups were denied participation?

Do you have a sense of why the government agreed to it?

The Swedish are big funders of Liberia’s development program. Their influence may have had an impact on the government allowing the Finnish judiciary to come here – but on the condition that they don’t rock the boat: ‘This is a society where people are still agitating for accountability for past crimes, we are only giving you a window here to carry out a small assignment: you’re getting your evidence and then you go’.

The elite are doing everything to ensure that the conflict is forgotten. The Finnish trial is going to reinforce the desire for accountability even though there is going to be frustration because those who wanted to attend, could not.

One benefit of the experiment is that the Finnish judges, prosecutors and lawyers get a better understanding of what they are dealing with and are better equipped to try the case by coming here. Another benefit is that the victims do not to have to travel all the way to Finland. Would you still see some positive aspects?

In terms of the logistics, yes. It’s a good thing that witnesses do not have to fly for many hours. The Finnish trial is also mobilizing communities. During one of the hearings I heard a witness saying that when the [Finnish] police came and took their initial deposition they were not sure whether they would come back again. But they came back and in that witness statement there was a lot of hope. For a witness to air such views of optimism is very relevant in the Liberian situation where the elite have arrived at a consensus that is, in my view, collective amnesia. They are doing everything to ensure that the conflict is forgotten. So at the end of it I think the Finnish trial is going to reinforce the desire for accountability even though there is going to be frustration because those who wanted to attend, could not.

Massaquoi is not a Liberian citizen. Did that play a role in the Liberian government decision to allow his trial to take place in Monrovia, because it was less sensitive and less likely to disrupt the Liberian political scene?

Certainly. It would be almost inconceivable for the Liberian government to allow a Finnish court to come and try a single Liberian. You can imagine the political fallout. I think the decision was primarily driven by Massaquoi’s nationality as a Sierra Leonean. Also, Scandinavian countries are big players in the development agenda of Liberia, and the country is in a state of recession, so there is much rationality in the government’s calculation.

Through the court proceedings, it has become apparent that the memories of local communities are countering the TRC official records.

You are the only Liberian scholar to have attended a few hearings of the Massaquoi trial and to have followed it closely. It appeared that the court didn’t have much knowledge of the timeline and chronology of the conflict, even though this may have some direct impact on the understanding of the case. What are your observations and reflections?

There is a timeline of the Liberian conflict that is very key. Let’s take the whole dynamic of what people here – and witnesses in court – call “world war 1”, “world war 2” and “world war 3”. Historically this refers to different waves of violence that occurred in 2003, a segment of the 1999-2003 second civil war. Between June and August 2003 the LURD warring faction [Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy] violently advanced on Monrovia and planned to take the city. During the proceedings, I observed that nearly all of the witnesses got this timelines wrong—but some of the media representatives remember the timelines accurately. For example, Jeddi Armah was the editor and a star reporter with Radio Veritas, a radio station owned by the Catholic Church which was considered as the most respected and balanced media. He remembers the exact dates of the three waves of attacks that gave their names to the three “world wars”: June 6, June 27 and July 19.

I used to live in the centre of Monrovia, in an apartment building on Water Street, located between the Old Bridge and New Bridge that has come up in the Massaquoi proceedings as a major landmark. It is very fresh in my mind. 2003 is the more recent period that we saw real violence, when the entire country shut down. You would think that people who suffered directly from this violence would tend to recall it more vividly. Surprisingly they remember these timelines differently. Some witnesses refer to 2001 or 2002 as 2003. What is driving this sort of amnesia and confusion is not very clear. Why are Liberians confusing these recent dates?

And of course what may be problematic is that there is apparently enough evidence from the records of the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone that accounts for Massaquoi’s physical presence in Sierra Leone at the same time in 2003 while he is being accused of causing harm in Monrovia.

Here is another intriguing aspect. The TRC went to the communities and took statements in Lofa. This region was particularly researched. The TRC report deals with different categories of alleged perpetrators and massacres. On the list of massacres in Lofa, the Revolutionary United Front [RUF, Massaquoi’s rebel movement for which he was the spokesperson] is not mentioned at all. RUF is listed for 86 kinds of human rights violations in the report but when it comes to attribution, while the Liberia Peace Council (LPC) for example is listed as having committed 11% of the atrocities, and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) some 47% of the atrocities overall, the RUF is listed as near 0%. The RUF are not acknowledged as a significant perpetrator group. Some of their main commanders – like Sam Bockarie, Superman, Issa Sesay, Johnny-Paul Koroma – are mentioned. Massaquoi is not included among them. But witnesses under oath said they saw Massaquoi commit war crimes, including torture and summary executions. Through the court proceedings, it has become apparent that the memories of local communities are countering the TRC official records.

PART 2: ACCOUNTABILITY IN LIBERIA

In the context of Liberia, we have to measure progress modestly. It is happening at a rather low and skewed level, yet the people talking are Liberian victims.

How does the Finnish trial fit into the long search for accountability that Liberians never got on the atrocities committed during the two civil wars? Were expectations too high? Should we understand this trial as just one of many steps in that long process?

In a post-conflict environment where expectations are high and transitional justice processes are normally governed by the elite – and the elite is mostly complicit in the Liberian war – we should try to measure progress in another way. This trial is an important milestone of progress. We have to acknowledge that unwittingly part of the government decision to accept this may be [the result] of some pressure by the civil society.

The court is looking at atrocities committed in Lofa county, the county that recorded the highest number of massacres – 32 sites – in the country’s history. It is also looking at the fighting that took place at Waterside, one of the most recent places where so many Liberians got killed in Monrovia, including from shelling. However confidential and privileged the access has seemed to be for ordinary Liberians to attend the proceedings, these communities have been reminded that justice is still possible. It may come in different forms and shapes but ordinary Liberians in Lofa and other places who have known violence for at least two generations are seeing opportunities in different forms: in the form of the Finnish criminal justice system, in the form of the government seeking diplomatic and development cooperation. What is still there at the end of the day is that victims are given a forum to talk about something that the TRC wanted them to talk about.

So this is an important opportunity and it is going to energize the civil society and [the support of] a bipartisan legislature that is growing. The Bar Association, breaking with Liberia’s elite tradition of procedural law, is now leaning toward justice. Tiawon Gongloe, the current president of the Bar, was victimized during President Charles Taylor’s regime. Under his leadership, the first draft bill was produced in 2019 for the establishment of an extraordinary tribunal. A revised version of this bill has just been completed. In the context of Liberia, we have to measure progress modestly. Witnesses and activists are going back home with something of a new hope. They wish that it would be more, they wish that the setting would be different, they wish that we would wake up every day to a front page in the newspaper, on TV and radio, but it is not like that. It is happening at a rather low and skewed level, yet the people talking are Liberian victims.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a number of former Liberian warlords tried in different Western countries. Have these trials abroad had an impact here in Liberia?

The ongoing prosecutions in the Liberian diaspora have had a very interesting impact. Some ethnic communities are questioning the coincidence of members of certain ethnic groups being arrested – Jungle Jabbah [tried in the U.S.], Alieu Kosiah [tried in Switzerland], Kunti K [awaiting trial in France], all come from the Mandingo ethnic group - and they are reading too much in this coincidence. The communities are confused; they are only driven by a simple explanation that after the war there are still ethnic purges continuing, even in foreign, Western capitals. That is one area of advocacy that the civil society really needs to work on to explain that this is not a continuation of ethnic pogroms and ethnic politics, that this is just a situation of international groups going after alleged war criminals using the mechanism of universal jurisdiction to pursue effective justice when they can’t in Liberia.

Without a war crimes court for Liberia ethnic stereotype will continue to triumph, peddling misinformation, half-truth and thereby impacting the social memory of local ethnic communities.

Even though there is still a lot of resistance among Liberian politicians to a national war crimes court, some say that former warlords are more worried today about the possibility of accountability. Is it true?

It is true up to a point. Generally you will find Liberians aspiring for justice but the very Liberians who express this aspiration collectively become divided on the issue of ethnicity. A man like Prince Johnson has successfully taught his account of the war and how ethnic Gios and Manos were the target for elimination. He has fed his communities with these half-truths so much that a majority of Gio and Mano who support him feel that there should be no prosecution against anyone from Nimba County. And the same is true with ethnic Mandingos. So we are dealing with the bigger issue of lack of a standardized historical record of the war being taught in school.

Every ethnic community is caught up in a situation where they have their individual account—social memory—of what they think the war was about. That’s why generally people tend to appear being in support of justice and accountability but when it comes down to a particular individual from a particular ethnic group they ask about how fair and transparent this is. We are in a complicated spot. That’s why, in my view, a war crimes court which would put together very clear and coherent domestic criteria for who is culpable would provide a more acceptable sense of justice. Without a war crimes court for Liberia to supplement the ongoing international prosecution of war criminals and solid historical records of the conflict, ethnic stereotype will continue to triumph, peddling misinformation, half-truth and thereby impacting the social memory of local ethnic communities.

Until those who committed heinous crimes during the war are prosecuted, post-war government officials will become emboldened to steal without remorse. You cannot deal with one in isolation of the other; they are mutually reinforcing.

It is 18 years since the war ended and the debate is still about creating a war crimes court. It feels like the momentum was lost. Are we moving away from that prospect?

I don’t think so. Are there challenges? Yes. It is now 12 years since the TRC issued its final report where it called for the establishment of an extraordinary tribunal. The TRC report in itself was not a strong instrument in preparing the ground for criminal accountability. It leaves a lot to be desired. But for many Liberians the names mentioned in this report [for their alleged responsibility in the war] were very accurate.

Another challenge is that civil society is fragmented. The agenda is the same but there are different actors having their own different strategies. Everyone wants to be seen as the lead actor in the debate. Transitional justice processes are often compromises and cooperation between the elites, the civil society and victim communities. We want the same outcome but we are going about it in ways that are undermining our own progress.

The international community is suspicious that the transitional justice agenda is being supported by outsiders. Part of this suspicion is grounded in the notion that Liberia is a low-capacity society and anything that comes with certain quality around justice accountability has to be the work of an outsider. It is sad but this narrative has been around for long and has continued to run its course. It doesn’t give much credit to Liberia’s justice community as it tends to rob activists and victims groups of some of the pioneering initiatives undertaken after the Accra Peace Agreement.

Another point is that the transitional justice movement in Liberia is mostly Monrovia-driven. There are about 207 sites of massacres across the country. The major centres of these massacres are in Lofa, River Cess, Grand Cape Mount and Gbarpolu. The Transitional Justice Working Group, comprising victims groups and civil society organizations, is largely a Monrovia consensus. They are not in those counties were the actual events occurred. In Monrovia we have all the fine language of transitional justice but people can easily forget what happened 18 years ago. In rural Liberia people wake up every day to visible reminders of that past. This constitutes a major hurdle in the fight for transitional justice in Liberia.

The opportunity here is that Liberians are beginning to see a strong correlation between wartime atrocities and post-war corruption. The growing call for an economic crimes court is a testimonial in this regard. The link between the two was blurred. Now people are seeing it: post-war government officials feel it’s OK to steal because those who killed people (and committed some of the most horrific massacres) are walking free and enjoy protection from prosecution. Until those who committed heinous crimes during the war are prosecuted, post-war government officials will become emboldened to steal without remorse, only with the vindication that they didn’t kill anyone. You cannot deal with one in isolation of the other; they are mutually reinforcing. Violence and corruption are being normalized. Sadly the international community does not see this link but it is at the centre of the agenda. People who are entertaining thoughts that the opportunity of justice is slipping away are those who are not seeing clearly the link between wartime atrocities and post-war corruption.

Another point is that the society is now stratified across three generations: the pre-war generation that saw the war unfold; the wartime generation, born during the war; and the post-war Accra generation, born after the 2003 Accra peace accords. The two most important are the last two generations who are yet to develop an independent view of what the war was about. Their views and attituded are largely influenced by the Liberian political leadership which really doesn’t want accountability. They are seeing the normalization of violence and the normalization of corruption with no memory of what Liberia was prior to the war.

PART 3: THE WORK OF MEMORY

The government went to build a static monument with no commemorative wordings, nothing. A few months later, the monument was being desecrated, vandalized by youth in the local community. What is driving this attitude?

You are working on how local communities have been taking care of remembrance when the state doesn’t. Where does this happen and what forms does it take?

I am fascinated by how local communities are using memorials as a strategy of justice, of closure, of trying to atone for their loss during the war. You have local communities who are re-appropriating what used to be the prerogative of a state, like having memorials, commemorations to rebrand the idea of patriotism, to reimagine citizenship or a new sense of a nation. In central Liberia, for example, you have the community called Samay that innovatively came up with a monument to all those who died in 1993-1994. It’s a crucifix and they’ve put a roof over it alongside a reading room.

Prince Johnson has erected a monument to himself, with a Bible in his hand, that says: “Here stands the revolutionary who saved Nimba county from destruction, an evangelist, a statesman and a diplomat”, and I heard he is trying to destroy it. In November 2020, when I went to the place, it was sealed up and I could not verify if it was broken down or still standing.

Another memory work I saw is in the outskirts of Monrovia at a place called Duport Road where the community erected a memorial signpost that said “victims of the Liberian war killed because of the tribe they belonged to”. It went into disrepair and the community reorganized to build a proper memorial. While this development was underway, the government, through the Human Rights Commission and with little or no consultation, went to build a static monument with no commemorative wordings, nothing. A few months later, people at the Commission started to complain that the monument was being desecrated, vandalized by youth in the local community. What is driving this attitude? Are the youth reacting to the government trying to impose a monument that doesn’t say much and didn’t come from a consensus in the community?

Two blocks away from where we sit now [in the Sinkor area, in central Monrovia], there is the Saint Peter’s Lutheran Church, where one of the most infamous massacre took place in 1990. That site is remembered today by two stars on the basketball court, in the church compound. They mark the sites of the mass graves of 600 persons. In that massacre was President Taylor’s father, Philip Nelson Taylor (who had claimed he didn’t support his son). In 1999, President Taylor’s mother along with family members went to Saint Peter’s Lutheran Church and erected a plaque in honour of Philip Nelson Taylor. The question there was: why would President Taylor not engage in a more fitting memorial for the majority of Manos and Gios who were killed at the church on the perception they were all supporters of Taylor? In a nutshell, there are a growing local community memorialization projects coming up. Whether those memorial projects adhere to a constructive effort towards Liberia’s past or whether they are destructive in the sense that they don’t help to restore damaged relationships is the most central question.

Interviewed by Thierry Cruvellier, JusticeInfo.net

Aaron Weah is a member of the Africa Transitional Justice Network and adjunct lecturer at the University of Liberia. He is currently a PhD Researcher at the Transitional Justice Institute (TJI), Ulster University, Belfast, Northern Ireland/UK. Formerly, he served as Country Director for Search Common Ground Liberia and Programme Associate for the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) in Liberia. He is also the co-author of “Impunity Under Attack: The Evolution and Imperatives of the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission”.