JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

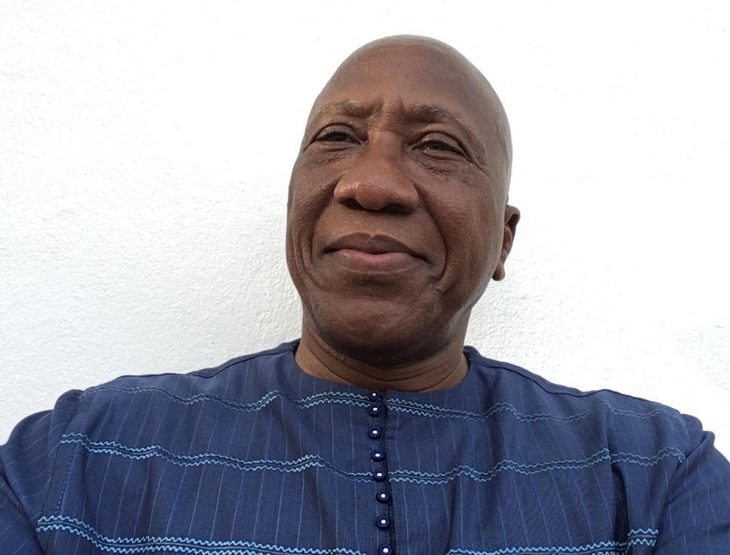

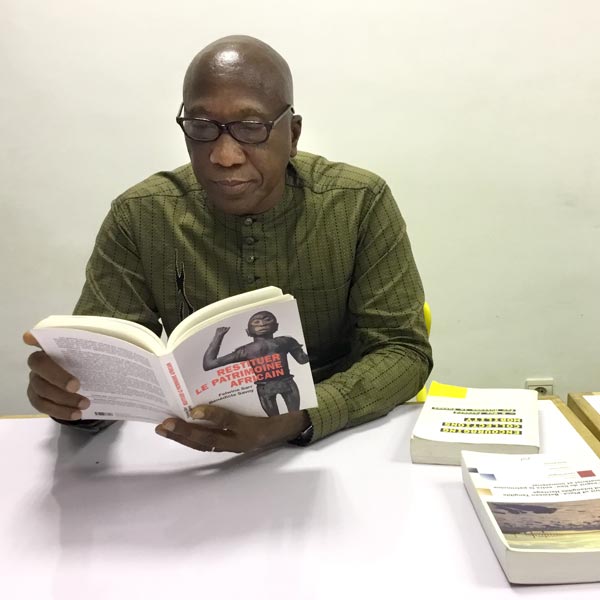

Alain Godonou

Director of the Museums Programme at the National Agency for Heritage Promotion and Tourism Development in Benin

Founder and first director of the School of African Heritage, Beninese curator Alain Godonou is a pioneer in ideas and action for returning to Africa cultural property seized or looted during colonization. French President Emmanuel Macron has pledged to restore to Benin a first 26 valuable pieces. In its wake Berlin followed by launching, on Wednesday, a major inventory of collections from the colonial era. Alain Godonou explains the importance for reparation, remembrance and reconciliation.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: For nearly half a century, several countries or communities have been calling for the return of objects that disappeared, were stolen or bought illicitly during the colonial period. At the end of the 1970s, UNESCO even produced a "standard form for requests for return or restitution". Then nothing was done for 40 years. What has changed recently and why?

ALAIN GODONOU: The main reason is Africans' awareness that something of theirs was missing. The first claims were made rather by countries such as Egypt and Greece. Sub-Saharan African countries were not yet in a position to file claims.

At the School of African Heritage [founded in 1998 in Benin], students and teachers were given the task of reviewing the inventories in their museums. They concluded that there was not much there, that most of the things had been to a large extent taken away. We travelled and knew the importance of the collections in some of the major colonizing countries. You know, when I was a conservation student in Paris, I didn't have access to African collections.

Why?

Because I was African and that could be dangerous.

Which years are you talking about?

The mid-1980s. When I asked to do my internship at the Musée de l'Homme on African collections, I was sent to work on mouldings. It may not have been an institutional policy, but it was complicated as an African to have access to the inventories of African collections.

Because people thought you would steal them?

Yes, or simply because when you enter the Musée de l'Homme or Quai Branly Museum [art and culture of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas], you may be shocked to see that there are so many things when there is nothing in your country. How come there's all this here and nothing there? Just that could bring a feeling of revolt. So it wasn't easy. And even now, because it is considered part of French heritage, I am not allowed to use the photos. The rights belong to the Quai Branly. I can't have a high resolution photo, it's not possible. I've been denied it.

When you enter the Musée de l'Homme or Quai Branly Museum [art and culture of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas], you may be shocked to see that there are so many things when there is nothing in your country.

That's when the realization came that we had, in fact, lost a lot. I published work on this and gave the statistics. When Egypt claims a few objects and Greece claims Parthenon marbles back, it is not in the same order of magnitude as when Africans say they have lost their memory.

What is the order of magnitude?

For African countries, it is a minimum of 75% that has gone. I helped draw up these statistics from the inventories of public museums.

In November 2017, in Ouagadougou, the French President announced his intention to organize, within five years, the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage that is in French public museums. Is this speech a turning point or just hype?

It is a major turning point that a French statesman, in his position, makes such an affirmative speech on restitution. There have been ups and downs in this area. South Korea, for example, has been asking since the days of President Mitterrand for France to return manuscripts of Buddhist temples, and today they are still discussing how much, when, what, etc. Some of them have been returned on long-term loan, but have never been declassified from French heritage.

It is a major turning point that a French statesman, in his position, makes such an affirmative speech on restitution.

The major obstacle that President Macron's speech removes is the one that says these objects are governed by French law and that in order to place them elsewhere we must review the laws, change the French heritage regulations and that it is almost impossible to do.

Aren’t you worried that it is just a little symbolic gesture that doesn’t really change the situation?

First of all, I think President Macron is sincere and wants to move forward. He has given us proof of this in Benin. A new team is coming [this] week to discuss with us how to move forward on this issue. But what can slow down this dynamic is whether African countries are ready. Benin has made some claims, but after Benin there is no one much else.

Your country is to receive 26 works that Emmanuel Macron has announced are being returned. How has Benin managed to convince France – or at least its president – to take this first step?

Because Benin has a consistent program to develop its museums. There has been a lot of thinking in the country, which is poor, has no oil, diamond or gold mines but has a very rich history and heritage. The thinking is as follows: we live from what we have and we have a rich heritage, so let us devote ourselves to it and show what we have, let us base part of our economy and development on it.

The criticism levelled at the countries of the South was that they did not have institutions capable of hosting [these collections]. We now have this big project, so we would like to have these collections.

This calls for institutions and museums around which we can create a certain social and economic dynamic. The criticism levelled at the countries of the South was that they did not have institutions capable of hosting [these collections]. We now have this big project, so we would like to have these collections.

Indeed, what do you think of this argument against restitution that says there is a lack of adequate "skills" in African museums?

This argument no longer holds since our policy sets up arrangements. It is not that there is no museum curator in Africa and that there cannot be one. It is just that up to now this heritage and museums sector has not been a priority and has not received the necessary means and capacities to develop.

But isn't the incapacity argument in itself a particular way of looking at things? Aren't museums just one way to preserve objects? And for these objects to have been found, did they not have to have been preserved in the first place? Isn't it a bad argument?

I wouldn't say completely bad. Another side of the reality is that there is a lot of trafficking in ancient African art. So if there is no guarantee of safekeeping, they will disappear. We know of cases of art that has been returned and ended up on the market. In the past, the museum institution as we know it today did not exist. There were other forms of conservation. Today there are museums, but there are also all kinds of trafficking networks and mafia that target this type of object. We cannot therefore stick to an intellectual position saying that we used to keep things this way in the past and so we should be able to do the same today. Traffickers don't think that way.

Can you remind us of the context in which these pieces ended up in France? What is this phenomenon of "colonial capture" - war booty, military looting, scientific raids - described as a "crime against peoples" by the authors of the report to President Macron, Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy?

There were several scenarios. First of all, there was war booty. In this case, it is mostly objects symbolic of the people defeated, such as regalia and emblems of power. We must draw a parallel with what the English did in the Ashanti country - today's Ghana - where there was a great battle to take possession of the golden throne, symbol of Ashanti royalty. This took place in the middle of the 19th century, when the colonial powers entered, taking possession of the land and what was truly symbolic of the peoples they defeated. These were not riches, they were what was symbolically important.

The colonial powers entered, taking possession of the land and what was truly symbolic of the peoples they defeated. These were not riches, they were what was symbolically important.

There are also soldiers who left taking things with them. It is a story we saw again and again over 30 years in many parts of the world, not only in ancient Benin, Dahomey or Ghana, but also in Asia with, for example, the sacking of the palace in China.

Is restitution easier for these artifacts, since looting by soldiers has been considered for more than a century a clear violation of international law?

Absolutely. In addition, we are currently living, more or less, in a period of peace between peoples. There is no reason to continue keeping the war trophies. It seems barbaric. It is not justified, morally or philosophically.

There is no reason to continue keeping the war trophies. It seems barbaric.

Then there are other series of objects [carried off] by missionaries, anthropologists, colonial officials. I have an issue with the somewhat excessive assertions in the Sarr and Savoy report considering this as raids. It was a time, we must not forget, when anthropology and ethnography made great progress. Of course, there were excesses. Yes, they took things, but it was not in a spirit of raiding or of conquest.

The first research institute in Africa, the Institut français d'Afrique noire (IFAN), was created at the beginning of the twentieth century by Theodore Monod with its headquarters in Dakar. IFAN had departments in all countries. Obviously, this was a way of extending the reach of the colonizing country in the conquered territories. But the first national researchers were born there. IFAN's work led to the writing of the first general history of Africa. Many things were born in this cauldron, in this effervescence. I do not attribute too many bad intentions to that. Of course it was a colonial period, but there was a kind of positive advance of republican ideas during that period. This type of work, this type of research stemmed more from that, in my view, than raids or looting of riches. Traders and traffickers were in other sectors of the economy.

What are you expecting of the 26 artefacts from the ancient kingdom of Abomey?

There is the political agenda and the conservation agenda. Since it is the politicians who decide, we are waiting for their decision. From the conservation point of view, the restitution must be done at a time of year that ensures that the returned objects arrive in good condition. They shouldn't travel when the climates are very different. Winter is not the right time. The restitution should always be made during the summer period [in Europe]. If not this summer, it will be next summer.

We take precautions as if we were transporting nuclear material!

There is also a whole insurance and preparation procedure requiring daily work that the layman does not understand. It's a long procedure. I'd say we take precautions as if we were transporting nuclear material!

These pieces do not only have a museum dimension, they speak to the imagination, they sometimes have a function. What do they mean to the people of Benin?

The museum is only a receptacle to allow their reintegration. These objects are regalia, symbols of royal power. To understand them, it is important to know that those who had custody of them let them go at the cost of their lives. That is, they would rather die than see these objects leave -- because they were the sign of their attachment to the land, to their ancestors, the symbol that they were men and women, that they were a people. The symbolism is therefore very strong.

When the English wanted to take the golden throne of the Ashanti, which symbolized the Ashanti nation, it caused terrible wars. These objects bear testimony to that, to the attachment and loyalty to one's roots, to what one believes.

You will no longer find objects of this beauty and workmanship. This creative force has been lost.

Aesthetically, they also bear witness to know-how that has now disappeared. You will no longer find objects of this beauty and workmanship. This creative force has been lost. But it is also a classical notion that creativity is encouraged by looking at things that represent the height of what we want to do. These objects will therefore also be used extensively in teaching not only historians but also artists and philosophers, to make them think about what they represent.

Finally there is also their aesthetic quality for our eyes. People will say with pride: well, at one point we were able to do that, so maybe we can make things of such quality again.

90,000 pieces are said to be listed in the public museums of France; Great Britain has 69,000 objects from Africa in the British Museum; Belgium has 180,000 in the Royal Museum; Germany has 75,000 for its future Humboldt Forum in Berlin; and then there is Italy, Spain, Portugal. How do you see the position of the other former colonial powers on the issue of restitutions?

It cannot remain a one-to-one between France and Benin, or between France and its former colonies. It must become an international debate and perhaps be the subject of an international convention, so that all countries have a framework to manage this type of issue. I am referring to a convention that talks about the circulation of artworks. The word circulation is important.

It must become the subject of an international convention, so that all countries have a framework to manage this type of issue.

With regard to Beninese, Senegalese and Burkinabe objects, there is as much need for them in the diasporas. Today, we are all from everywhere. Therefore, these objects must have a status that allows them to circulate. And for that to happen, rules must be set

The authors of the Sarr and Savoy report fear that talking about circulation is mainly a way of not talking about the restitution issue…

Yes, and it's true. There is ownership, which must be clear. The issue of conservation capacities should be separated from the legitimate right of ownership. From this point of view, the objects should be considered as on deposit, on loan for a more or less long period, in the museums of the former colonial powers. The rationale of proposing long-term deposits in countries of origin as a solution must be reversed! This means that countries of origin, regaining ownership, will have rights to the images, which are important for different uses, and a say in the circulation of works of which they have regained ownership.

The rationale of proposing long-term deposits in countries of origin as a solution must be reversed!

Then there is where they go. This question is important because it also arises internally in Benin. The objects we're talking about started in Abomey. Should we send them back to Abomey when our objective is to build the nation and have them regarded as the whole country's heritage? There is also work to be done here, and this is a debate in Benin.

There are significant differences of interest on the African continent around the issue of restitution. Sarr and Savoy note that in some countries "amnesia has worked and the process of erasing memory has been so successful that some communities are unaware of the existence of this heritage and the depth of the loss suffered"…

That is for sure.

On the other hand, "in countries where the loss of heritage is linked to violent, painful or tragic events", as in Benin, "the memory is still alive and it is a hot issue", they write. Do you also see these factors at play?

Yes, absolutely. There are differences because of the role of forgetting. It depends on how history is taught, how colonization has worked. The colonial occupation was not violent everywhere. It was not a war of conquest everywhere. It was sometimes done "peacefully", in "good cooperation", with one side tricking the other and then gradually establishing itself. In some countries, such as Benin, there was very serious violence and wars. So these wounds remain.

But the story is complex. It should be understood that the French were not at war with all the peoples that make up today's Benin. They had allies who were at war, for example, against Abomey. It is a more complex story than we are saying, and it should not be simplified for heritage reasons. They remain complex. These objects, which were taken from Abomey, can be a problem in Benin. The peoples against whom Abomey was waging war, such as the Yoruba - many of whom found themselves slaves in the Americas - in their past and present memory are justified in thinking: why all this fuss around the people who massacred us?

You remind us of the story’s complexity, but you remain very clear that restitution must happen...

Yes, absolutely. These objects say much more. They say things about our societies, about our ways of thinking, and it is important to have them to reflect on them, not to make them the property of a small group of the population.

To speak openly about restitution is to speak of justice and reparation. Is that what scares Europeans?

I believe that what makes Europeans afraid is the amnesia over the violence that colonization represented. They do not want that page reopened, because colonization is widely presented as positive. However, tens of thousands of people were killed by massacres. Césaire said that colonization prepared Nazism. From the moment we kept quiet about the massacres of the natives, Nazism could do its job. This type of discourse has not been listened to.

And do you think it is heard today?

Oh, I think it is still very uncomfortable!

The rapporteurs Sarr and Savoy seem optimistic that European societies are ready to confront this past. Are you also optimistic?

I don't know. I'm watching. When we look at the political movements that are resurgent, we may be taken aback by a retreat of ideas. These are societies that are today very diverse, more so than in the past, but we still see widespread clichés, prejudices, forms of racism and intolerance of all kinds. This means that we must continue working to make intelligence prevail.

Is there not a fear that the restitution of cultural property is just a first unconscious step in the work that Europeans have never done on their own past, and that it could lead to an escalation of claims and demands for reparations for colonization?

Some people say openly that things will escalate. There are movements making claims. But I don't think that's the main thing. I don't think we can live on claims and reparations. We must talk about the violence suffered, the injustices suffered, need for reparation. This is morally and philosophically important. If humanity sets itself a common destiny and thinks of itself as a community, that must happen.

I don't think we can live on claims and reparations. From our point of view, we are entering a field where there is a need for appeasement.

But from our point of view, we are entering a field where there is a need for appeasement. We are not in opposition to France. We have a common history, which has been brutal, sometimes very hard, but we are still here and we must move forward. All our problems are related. Working this out together is important.

Restitution is also a work of memory. What is at stake, in your opinion?

For the victims, it makes them proud to know that they did not come from nothing, that they had things in their home country. Part of the colonial discourse was to bring civilization. But there was already civilization! So erasing this type of discourse that treated us as savages which we were not, is important. Restitution contributes to this. This is about becoming more aware of our common humanity.

On this point, you agree with Felwine Sarr, who says that one of the challenges of these restitutions is a reinvention of the relationship between peoples, and that these objects must be "/mediators of a new relationship".

Absolutely.

Is the restitution of cultural property therefore also a reconciliation issue?

That's for sure. From our point of view, restitution is not a conflict issue. President Macron's approach is also more about reconciliation. Let us say that most countries experience it as a moment of pride, of affirmation in the face of great injustice that has persisted, something that says justice will be done, that our voices are heard.

Most countries experience it as a moment of pride, of affirmation in the face of great injustice that has persisted, something that says justice will be done, that our voices are heard.

Interviewed by Thierry Cruvellier.

ALAIN GODONOU

ALAIN GODONOU

Comlan Alain Godonou is currently Director of the Museums Programme at the National Agency for Heritage Promotion and Tourism Development in Benin. He is also vice-president of the Committee for Museum and Heritage Cooperation between France and Benin. He directed the School of African Heritage for twelve years (1997-2009). A former director of cultural programmes (museums, intangible heritage, intercultural dialogue) at UNESCO, he is the only African, and one of the youngest professionals, to have been awarded (in 2005) the International Council of Museums’ award for commitment and professional excellence in conservation, a triennial distinction received in The Hague.