There are two main groups who benefit from international criminal justice, a senior official confided in private. They are, he said, international jurists, who forge prestigious careers with very comfortable salaries; and mid-range commanders who serve the prosecutor as informers and key witnesses, enabling conviction of their former brothers-in-arms in exchange for freedom and impunity. The person reaching this harsh conclusion has served in several sensitive posts in UN tribunals and is not a cynic.

In 2002, former Sierra Leonean rebel commander Gibril Massaquoi decided to be among those who benefit. Knowing that he would be a potential target for the prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) being set up in Freetown after a bitter civil war, Massaquoi, a former spokesman for the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebellion, introduced himself to the court's head of investigations, Alan White. He offered his collaboration. This allowed him to benefit from the protection of the UN court and not be prosecuted. He then obtained, in 2008, a seemingly calm "relocation" to the city of Tampere, in Finland.

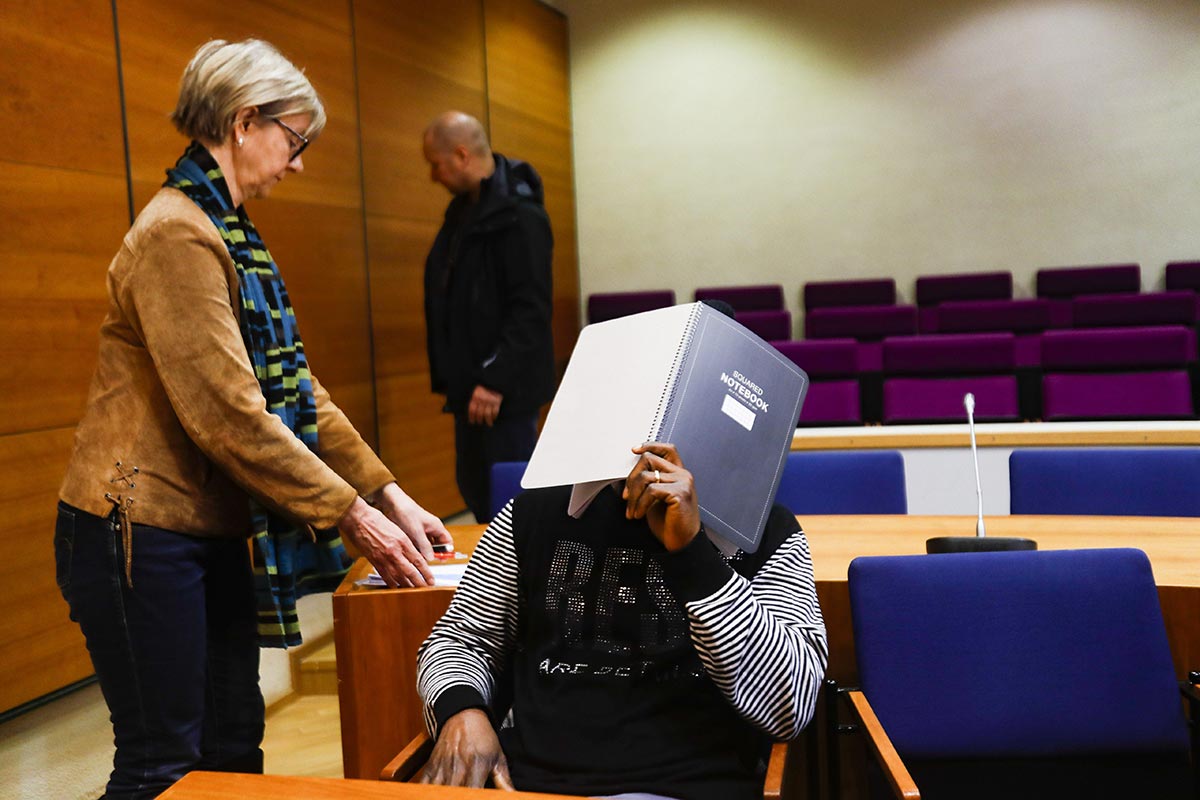

Massaquoi's strategy paid off... until March 10, 2020, when Finnish police came to arrest him and notify him that he was now being prosecuted for crimes against humanity committed in Liberia between 1999 and 2003. This has no known precedent. Never before has a former "top grass" of an international tribunal - at the SCSL Massaquoi is considered by White to be "probably the most important of all" - been arrested and charged by a national court without the agreement of the institution with which he collaborated.

He could have been prosecuted but he wasn’t. There was an implicit statement that he wouldn’t be. This may make a mockery of any witness protection program.

A mockery of witness protection?

Since then, the Massaquoi affair has been sowing controversy in international justice circles, notably among former members of the SCSL. “Here is a person relocated because of threat, and after a few years he is now prosecuted. It’s a very odd situation and it has not happened before,” says a former top UN court official who did not wish to be named. “Don’t get it wrong, we are dealing with criminals, nobody is an angel. But that is the quid pro quo of the whole thing: he could have been prosecuted but he wasn’t. There was an implicit statement that he wouldn’t be. This may make a mockery of any witness protection program.”

There are two vigorously opposing sides on this affair. The first is formed around David Crane, Chief Prosecutor of the SCSL from 2002 to 2005, Alan White and his assistant Gilbert Morissette. Crane appeared like a judicial TV evangelist. He has a lean, athletic physique and a taste for big statements. Convinced that he was on a mission against Evil, this white knight liked to say that, to do so, one must know how to "dance with the devil". He liked things black and white. The nuances of a civil war in a country that was completely foreign to him made him impatient. But he was a boss who imposed discipline and hard work. Few international prosecutors have been so quick to define a clear and focused prosecution strategy; none of his successors have questioned its effectiveness and relative consistency.

White had at the time a reputation for travelling the region, saying Al-Qaeda and terrorist networks were thriving there. He liked to magnify his role and the risks he was running. He did not have a lot of admirers at the court. On the other hand Morissette, with his shoulder length hair, sparkling eyes and moustache of a Quebec lumberjack, was a warm, laughing, drinking, swearing, rough and ready policeman. He liked police raids, the hunt and relations with his informers that were at the same time tough, loyal and affectionate.

If you want to get to the top, you need somebody to bring you to the top. It is not uncommon to provide immunity or not prosecute insider witnesses that provide crucial information and credible testimony that leads to a successful prosecution.

Massaquoi was the first "insider" to put himself in the hands of these men. Clever and educated, he quickly earned himself a special status with White and Morissette. The former rebel obtained protection and privileges. He was cosseted like no other informer and, at first, his account of the war heavily influenced the prosecution. There was no lack of evidence of Massaquoi's personal responsibility for the crimes committed by the RUF. But Crane decided that there would be no prosecution against him. The prosecutor would only target the handful of individuals he believed to be most responsible. Massaquoi would not be among them.

“If you want to get to the top, you need somebody to bring you to the top,” White told Justice Info. “It is not uncommon to provide immunity or not prosecute insider witnesses that provide crucial information and credible testimony that leads to a successful prosecution.”

We're talking about organized crime. The only way to investigate successfully is from the inside. When you have insiders, they are the eyes and ears of the police.

“Insiders are our eyes and ears”

Luc Côté worked for four years as a prosecutor attached to the investigators of the UN Tribunal for Rwanda. From 2003 to 2005, he was head of prosecutions at the SCSL. "Everywhere, insiders are important," he says. "In Sierra Leone, they were probably necessary. I don't remember seeing very incriminating evidence against [Massaquoi]. It may have played a part" in the former rebel's good fortune. "Not everything is always said between the investigation services and the lawyers," Côté said. An investigator will not necessarily launch an in-depth investigation into a collaborator, so as not to "burn him". In international tribunals, this practice is reinforced by the fact, says Côté, that for the defence team, "it would be more difficult to carry out the investigation, as they have less means to do so".

Out of professional necessity, the investigator develops a special relationship with his or her "informant". "The investigator knows his family, watches his back for years," adds Côté. "Gibril had the personality to attract that."

Morissette swears a lot when asked about the reality of such investigations. "We're talking about organized crime. The only way to investigate successfully is from the inside. When you have insiders, they are the eyes and ears of the police. You establish a level of trust, you test the source, develop a relationship, which is always professional. You scratch my back, I'll scratch yours." It's a quid pro quo arrangement. And you get your hands in the dirt. "You have to take the necessary measures, otherwise you're just watching the trains go by. Money is given to sources for valuable information, transport and communications, for example. This is a perfectly normal practice, very well recognized in Canada and the United States, morally accepted by the courts. We do not have a crystal ball. How could we do otherwise? They are not cooperating because they love us."

Pursuing prosecution twelve years later is a politically damaging action that will impact future war crimes prosecutions.

A “politically damaging act”

When White and Morissette learned of Massaquoi’s arrest, they saw red. “I am concerned why the Finnish government is pursuing prosecution against Gibril twelve years later after accepting him into their country with knowledge of his past,” says White. “It was common knowledge that the RUF was directly supported by convicted war criminal former Liberian President Charles Taylor and frequently transited back and forth to Liberia to obtain arms and ammunition. Clearly as a member of the RUF Gibril, along with other rebels, travelled from Sierra Leone to neighbouring Liberia to meet with Taylor and his rebels. Accepting a relocated witness with knowledge of his past and pursuing prosecution twelve years later is a politically damaging action that will impact future war crimes prosecutions. I am deeply concerned about the motives and reasons behind this investigation and prosecution.”

White's support might be welcome for Massaquoi, since those currently in charge of the Special Court, transformed after its closure into a "residual court", are unlikely to lift a finger. Both Registrar Binta Mansaray, who has jurisdiction over witness protection, and Prosecutor James Johnson, who made extensive use of insiders between 2003 and 2012 when he was Senior Trial Attorney and then Chief of Prosecutions at the SCSL, are refusing to speak out on this case, even though it challenges the authority, interests and reputation of the UN court and the prosecutor's office in particular.

To put it bluntly, and despite assertions to the contrary, Massaquoi was ultimately of very limited value to prosecutors in court.

“Limited value in court”

White wonders about possible political motivations behind Massaquoi's arrest, or the desire of some individuals to get publicity. This targets in particular Alain Werner, a prosecutor at the SCSL between 2003 and 2008, founder and director of the NGO Civitas Maxima, whose research is at the origin of the decision of Finnish justice to open an investigation on Massaquoi.

The other camp in this controversy clearly supports Werner's initiative. These are essentially the prosecutors who worked on the merits of the cases and conducted the trials before the SCSL. In the 2000s, within the prosecutor's office in Freetown, they struggled to co-exist with the Crane camp. Publicly or anonymously, they now speak of the gulf that separated them.

“Unlike the chief and deputy chief of investigations, I was extremely acquainted with the legal value of evidence provided by the earliest ‘cooperators’ and its ultimate value,” says Christopher Santora, who worked in the SCSL prosecutor’s office from 2002 to 2010. Santora worked on three of the SCSL's four trials: that of members of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) military junta; that of the RUF; and that of former Liberian President Charles Taylor, which was the court's trophy.“To put it bluntly, and despite assertions to the contrary, Massaquoi was ultimately of very limited value to prosecutors in court and wasn’t even considered for the Taylor trial.”

Massaquoi was by no means the most important of the insiders as White and Morissette maintain. Some go even further: in their eyes, Massaquoi wasted time, witnesses and money.

Lies and loss of credibility

The jurists we interviewed insist on two points. First, Massaquoi has never admitted any responsibility for crimes committed while he led troops and was one of the ten members of the RUF high command. "He lied about his own responsibility. This severely undermined his credibility. It pollutes everything," says Santora. Second, Massaquoi is alleged to have erroneously downplayed the role of the RUF, including misleading the prosecutor about the role of the rebels in the deadly invasion of the Sierra Leonean capital, Freetown, in January 1999. This was a central event in the trials and in the history of the civil war.

Santora was present when Massaquoi introduced himself to the SCSL investigators in 2002 in Freetown. “You have to be very careful with the first guy who comes, so that he doesn’t force the narrative,” he explains. “When you arrive, you’ve got to have an exceptional level of humility. There was an aspiration that Massaquoi was the perfect collaborator. There was also a need to put together a case quickly.”

After his testimony in the AFRC trial, Massaquoi was excluded as a witness in the two other trials of the RUF and Taylor, where his testimony had been planned and expected. From then on, prosecutors affirm that Massaquoi was by no means the most important of the insiders as White and Morissette maintain. Some go even further: in their eyes, Massaquoi wasted time, witnesses and money. "He warranted protection but I am not sure to what extent," says another former member of the prosecutor's office between 2005 and 2008, who wished not to be named. "Witness protection is limited to full cooperation. That didn't happen" with Massaquoi, says Santora. "He provided pieces that were helpful. But it becomes useless if you don't say what you did [yourself].”

The Massaquoi case sets the limits of protection for those who collaborate with international tribunals and the promises of impunity made to them.

The fragile promises of international courts

Alain Werner is animated by an energy so intense and so permanent that one would think he was naturally connected to a generator. When he talks to you, he seems to want to absorb you physically. He is a workaholic, an idealist whose convictions are of a rare sincerity. Accused of having, in short, betrayed the traitor, Werner defends himself. "I never had any intention of breaking the system. I have personally worked with insiders. I'm convinced we wouldn't have won the Taylor trial without them. I understand that concern. But it needs to be understood: Gibril Massaquoi is not [accused] for what he did in Sierra Leone, but for what he did in another country and in another war, in Liberia. We would not have sent to the authorities a file against him for the crimes he allegedly committed in Sierra Leone. That is the truth.”

The Massaquoi case sets the limits of protection for those who collaborate with international tribunals and the promises of impunity made to them, which are generally unwritten as for Massaquoi (see box) and which are not binding on states that agree to offer them asylum. “What promises can the International Criminal Court (ICC) or any hybrid or international tribunal really make of non-prosecution, or reduction of charges, without the cooperation of national authorities? And is it even allowed? It’s hard to have a standard policy on this. It is an immensely tricky issue,” admits Eric Witte, Senior Manager of the National Trials for Serious Crimes at the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), an NGO. “There is a lot of room for an insider to be a suspect of another jurisdiction. It could happen in Central African Republic or in the Democratic Republic of Congo”, two countries where the ICC has cases and where national courts also have jurisdiction. “There is a need for some kind of coordination,” concludes Witte.

What some question is this: where does the "moral compass" of the SCSL lie? Where is the moral compass of the UN?

Where is the UN’s “moral compass”?

Certainly, the misfortunes of Massaquoi came from the organization Civitas Maxima and its Liberian partner, the Global Justice and Research Project. But the one who acted decisively was Thomas Elfgren, head of the National Bureau of Investigation in Finland. Again, it's a bit of a family affair: Elfgren worked for several years in the prosecutor's office of another UN tribunal, the one for the former Yugoslavia. He says he is very familiar with confidential sources, informants, and international tribunals. However, when confronted with the evidence gathered, he had little hesitation.

To some extent, the Massaquoi case would illustrate a conflict between legal cultures, between North Americans - Crane and White are Americans, Morissette is Canadian - and a more European tradition - Werner is Swiss, Elfgren is Finnish. Practices that seem natural in North America do not apply in other countries. Therefore, what some question is this: where does the "moral compass" of the SCSL lie? Where is the moral compass of the UN?

When thousands of combatants have caused tens of thousands of victims and in the end only thirteen individuals are charged, as at the SCSL, we are less concerned about those with whom we collaborate.

Realpolitik according to the gravity of crimes

Santora downplays the importance of this judicial divide. “Even in American culture, you still have a level of punishment,” he says. “It’s not that you get off scot-free. That should be the approach. At least all their conduct should be on paper.” Witte of OSJI was the special assistant and political advisor to prosecutor Crane from 2003 to 2005. He recognizes that some judicial systems “have more ability to cut deals, but I think it’s about the individuals involved. The investigation section placed a lot of emphasis on cultivating insiders and there are lots of questions on the way White and Morissette were running it. Some of the insiders had received so much money that they had no more credibility at trial”.

Côté also stresses the role of individuals. "Crane isn't a great lawyer, he's very political. He was willing to negotiate with Benjamin Yeaten," the man who served as a link between the RUF and Taylor. "Realpolitik, that's what it is. The moral scale is more elastic at the international level because there is a scale of gravity". When thousands of combatants have caused tens of thousands of victims and in the end only thirteen individuals are charged, as at the SCSL, we are less concerned about those with whom we collaborate.

So was it a mistake to send Massaquoi to Finland to be forgotten? Yes, is the clear general reply.

Impunity for prosecution witnesses

“Why are we having these trials?” asks the former prosecutor who requested anonymity. “One of the reasons is to create an historical record. There is that moral responsibility when we fish out witnesses like Massaquoi. We need to ensure that we are not taken for a ride. Why wasn’t he charged for perjury? This is about impunity for untruthful witnesses. This is why courts do not function well. [The problem] is across the board, and certainly at the ICC.” In fact, in international tribunals, the risk of being prosecuted for perjury when one is a witness for the prosecutor is nil. In the past 25 years, only defence witnesses have been convicted of false testimony.

Eric Witte does not think, in the end, that the Massaquoi case threatens the functioning of international justice. “It was Massaquoi’s decision to make his presence known [in Finland, see our Special report Part 1], he is prosecuted for other crimes and there have been [other] insider witnesses who came to honestly regret their crimes. Massaquoi is not the hardest case. I don’t see [it] as the test case.” Luc Côté agrees: "This case is not a threat. It will be quickly buried and forgotten. Those who will be burned are the Finns!”

So was it a mistake to send Massaquoi to Finland to be forgotten? Yes, is the clear general reply. For the former rebel who has been through combat, prison, bush camps and internal purges, it was a risk too many, and one of the few he probably took on the advice of others.

THE RWANDA TRIBUNAL’S TAINTED “GRASSES”

"My conscience is clear. I know I did not participate in the genocide," said Dieudonné Niyitegeka, the best protected witness in the history of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), in February 2002. His words are similar to those spoken by Gibril Massaquoi in our meeting in Freetown in March 2003. Massaquoi and Niyitegeka have some things in common. Both were the "top grass" in the service of an international prosecutor. Both recruited other "insiders", assisted in the arrest of some of their former comrades-in-arms, testified against them, obtained immunity from prosecution and denied personal responsibility whereas there were under serious suspicions about them. Both also had Canadian police officer Gilbert Morissette as their "handler".

In April 1994, when the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda began, Niyitegeka was treasurer of the Interahamwe, the militia that became the spearhead of the massacres. He was one of the five members of its national committee. Two and a half years later, he became the main informant for ICTR investigators. He recruited as an "informer" another member of the Interahamwe national committee, Phénéas Ruhumuliza, who died in Côte d'Ivoire after being "relocated" by the witness protection services. Two other key Interahamwe leaders were to join this group of collaborators -- Ephrem Nkezabera and Joseph Serugendo, two of the six commission presidents of the militia's central organization. And along with them was another local militia leader, Omar Serushago.

All of them bore responsibility in the genocide. Serugendo, Serushago and Nkezabera were forced to admit it, plead guilty and be tried before they could be presented as credible witnesses before the ICTR. The first two were convicted by the ICTR, with reduced sentences. Nkezabera's trial was delegated to the Belgian judiciary, at the request of the ICTR prosecutor, not without the former militia leader having negotiated the transfer of his family to a safe country.

Niyitegeka, on the other hand, has escaped any trial. He made it a condition of his testimony that he be given a written guarantee he would not be prosecuted. As the prosecutor's office desperately needed his testimony in the trial of the former heads of the notorious hate radio RTLM, prosecutor Carla Del Ponte granted this immunity in writing two weeks before Niyitegeka testified. The former treasurer of the Interahamwe enjoys full protection, under a false identity, in Canada. Unlike Massaquoi, he never made the mistake of putting himself on display, scrupulously respecting the rules and escaping prosecution.

To find out more about the role of the Interahamwe leaders at the ICTR, read “Court of Remorse, Inside the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda” by Thierry Cruvellier, Wisconsin University Press, 2010.

YOU MISSED THE FIRST EPISODE ?

THE MASSAQUOI AFFAIR: SPECIAL REPORT ON THE JUDAS OF SIERRA LEONE (PART 1)

Gibril Massaquoi, who was the top informer for the prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, was arrested in Finland on March 10. Twelve years after getting asylum and protection measures, the former Sierra Leonean rebel commander and spokesman is now being prosecuted for crimes allegedly committed in neighbouring Liberia. A judicial thriller with an international impact. In the first part of this exclusive report, we look at how Massaquoi’s past caught up with him. [READ MORE]