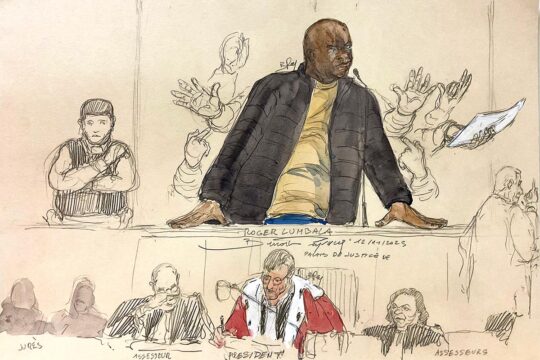

On a hot summer day in the Stockholm District Court, two sets of satellite images were pitched against each other, each side hoping to strengthen its case.

“You can grasp a photo of a burned village, but satellite images covering vast areas may be harder to digest. It’s new technology, yet the justice system must take advantage of this,” satellite expert Erik Prins, on his way into courtroom 34, remarks on June 24.

25 years ago, in a war zone with few if any journalists on the ground, there where eyes in space that observed. Powered by the sun and launched by NASA for scientific purposes, satellite images have now been introduced as evidence in Sweden’s longest ongoing trial.

Former Lundin Oil chairman Ian Lundin and ex-CEO Alex Schneiter are accused of aiding and abetting gross violations of international law for events that occurred in Sudan (now South Sudan) between 1999 and 2003. Both deny wrongdoing. The trial, which began in 2023, is expected to conclude by May 2026.

Two conflicting versions of what occurred in Sudan during those years are in direct contention. On one side, witnesses and prosecutors testify that thousands were displaced when government forces and militias cleared areas for oil extraction. On the other, the company contends that it wasn’t oil driving the conflict, that few people lived in those areas, and that the fires were due to traditional slash-and-burn practices, not conflict.

Earth observation satellites

Expert witness Prins, called by the prosecutor explained that the Landsat satellites – jointly operated by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey – have collected data on the planet’s land surface since 1972. This makes Landsat the longest continuous satellite-based archive of Earth observation.

The images from Sudan between 1997 and 2003 are sporadic – but in theory, the satellites passed over Block 5A every eight days. “The white areas in the satellite images,” Prins explained, “are the result of cattle grazing and trampling down the grass. From pasture management we know that cattle expose bare, sandy soil, and satellites pick this up. It’s a stronger marker than cropland, because crops may have been harvested.”

Prins recalled being approached by the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS) in 2006, who asked if he could shed light on “rumours” surrounding Block 5A. “I was known as someone who had expertise in environmental issues and could assess how the oil industry affected areas. ECOS’s request was simple: to examine land-use patterns and how they changed over time.”

Mass displacement of people

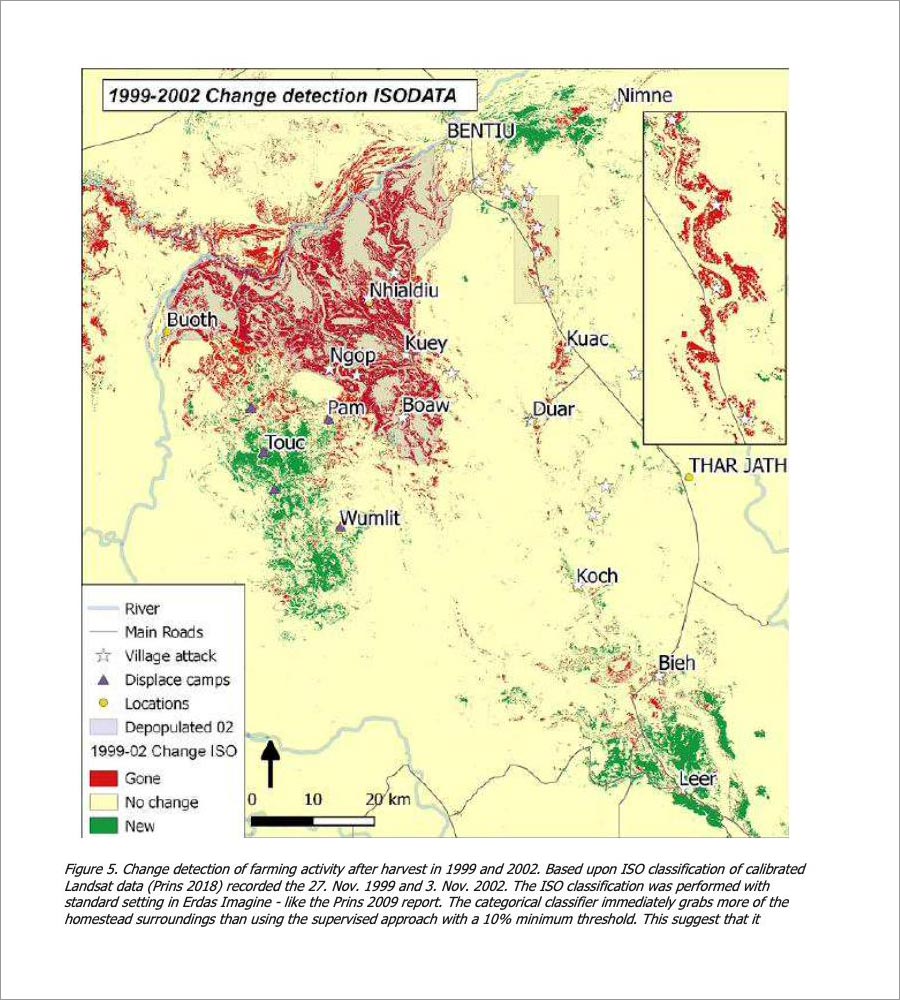

“One image is worth more than a thousand words. I want to show the images to show the truth.” In his presentation to the court, which Prins also published on his website, it was clear: between 1999 and 2003, large changes were visible in South Sudan – mass displacement of people and villages destroyed.

His analysis showed that people settlements disappeared from the “oil road” and areas near oil extraction and he argued that the images offered “objective evidence,” which also matched the testimonies of refugees.

He also argued that the Nuer people’s land use was particularly visible in satellite imagery, since they both grazed cattle and cultivated fields around their homesteads. “The roofs of huts can easily be seen in satellite images, as can the areas of cultivation,” he said, describing how “aggregated data from spectral channels” could reveal farmland.

He compared images taken in November over several years, since by then the rains had ended and fields had been harvested – and slash-and-burn fires were less frequent.

“Oil road” appears in 2000

Satellite imagery has become an important source of information and evidence in international law. But according to a recent UN and Asser Institute study their use is hindered by a lack of technical competence among legal experts on one hand, and satellite specialists’ unfamiliarity with the legal field on the other.

From images in 2000, the court could see the “oil road” between Thar Yath and Leer for the first time, along with a grid of seismic lines etched into the landscape. “We also see garrisons along the oil road in images from 2004,” Prins told the court. From 1996 to 2002, his comparisons showed fire damage outside villages at first. By 2002, many had moved toward Bentiu – the cattle leaving visible tracks around the town.

In a summary slide, Prins compared the evolution between 1999 to 2002. Green markers showed that activity dropped by 25 percent. “In the years in between, you can see burning inside villages, which could be a sign of conflict. If bushfires enter settlements, it may indicate fighting.”

Another slide highlighted in red the fields cultivated in 1999-2000, which later disappeared.

“Satellites detect – ground reports confirm”

He also compared satellite data to Lundin’s own security reports on incidents, showing patterns in three areas: the northern part of the all-weather road, Nhialdiu, with its major attack in February 2002, and other villages where displaced people later concentrated in Wicok and Chotchar.

One of his slides carried the heading: “Satellites detect – ground reports confirm.” Prins pointed out how the testimony of another trial witness, Diane de Guzman, who had drawn maps while walking through the region, matched what satellites revealed from above.

Finally, he presented a map comparing images from 1999 and 2002: in red, villages that were “gone,” and in green, new ones. The data show that fires in Nhialdiu peaked in 2001–2002.

Today, he added, anyone can search the entire Landsat archive via Climateengine.org, covering more than 40 years. “I was criticized for using too few images, but the entire archive is now searchable. The conclusions I presented back in 2013 [to ECOS] have only been strengthened,” he added.

He concluded that his findings rested on three layers of robustness – “belt and suspenders”: the scientific method itself, corroborating witness testimony, and newly available data.

“The number of error sources is too many”

According to the defence, these satellite images were central to the decision to open a preliminary investigation: “It was a way to give the investigation more material and ‘something tangible” said the lawyers in court, during last spring.

The defence’s experts from Hatfield and Company reviewed the images and produced two reports, the first titled Remote Sensing Review. The experts argued that the prosecution’s use of the images is “flawed” and cannot be given any evidentiary value.

According to the experts, no conclusions can be drawn about human activity from the images: “It is difficult to identify roads or villages because of the lack of human footprints.” “The number of error sources is too many, depending on season, cloud cover, the lack of fixed reference points, as well as the waterlogged ground and drainage along the road. The conclusion is that there is no scientific basis for the conclusions drawn in the Prins report.”

The defence also argues that one source of error is that what prosecutors see as burned villages are in fact grass fires caused by slash-and-burn practices. “From the drilling rig at Thar Yath, staff often saw villagers burning the grass at the end of the dry season.”

The defence also pointed to the book The Nuer from 1940 – which they had earlier used to argue that ethnic conflicts in the region were age-old – noting that it too described how grass was set on fire as soon as it dried, before the rains came and new shoots could grow. They also cited a global fire database showing that over half of South Sudan’s land burns each year – a pattern consistent with traditional farming, not forced displacement.

Their conclusion was that “burnt grass is more a sign of human presence than absence.”

“Before the road – there was no road”

Prins was not the only ‘satellite witness’. During the investigation, prosecutors had engaged their own expert: engineer Torbjörn Rost.

Rost tells the court, on June 25, he specialized in “object-based methods,” used in studies of refugee camps in Somalia and elsewhere. For over a decade he worked almost exclusively for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, using satellite images to estimate populations in inaccessible areas, including disaster zones.

When asked by police in 2013 to examine Block 5A, he began reviewing available images from 1997 to 2003. Like Prins, Rost focused on the available data. But he made it clear: his task was not to compare the same place across years, but simply to document what could be seen at each point in time. The key difference, he explained, was that Prins conducted “change analyses.” On police instructions, they had not collaborated.

Prosecutor Annika Wennerström showed the court a 1997 digital image with Block 5A outlined. “This is the maximum detail you can get. Only in Hollywood do you get closer. I assess this as human activity because the vegetation is stripped. But that is an assessment, an interpretation. To verify, I compared with high-resolution images,” she said.

Switching to a 1995 image, she asked why he placed a “dot” on it. Rost repeated that the reddish soil had been altered by human activity. “The police wanted to see huts, and I told them: ‘That’s not possible.’ I can’t say it was a settlement, but I can say there was human activity.” Throughout, he spoke of “human activity” – ground worn by people or livestock.

His answers were technical and cautious. Others would have to draw conclusions.

He described the dark areas inside villages as “burned grass,” sometimes showing fire at the edges. Unlike Prins, he placed no broader significance on this.

On the court’s four large screens, satellite images scrolled by: riverbeds, clouds, the White Nile. One image showed the road construction south from Bentiu. By November 29, 2000, the all-weather road had passed Duar en route to the rig at Thar Yath.

Asked whether military vehicles could traverse the area before the road, he said: “All I can say is that before the road – there was no road.”

Burning, and human activity

From March 8, 2002, images showed “some burning” along the new road toward Nhialdiu – slash-and-burn farming. “Large areas are burning, and you can see human activity,” Rost said. On April 9, 2002, the road reached Nhialdiu. By June 12, 2002, it cut through the town.

Nhialdiu is central to the indictment: prosecutors argue the government required Lundin to fund an all-weather road there to secure seismic surveys near the town, which was also a base for militia commander Peter Gadet.

After Prins’s testimony, the defence had no questions. After Rost’s, they had one.

They produced an earlier police interview in which Rost said that between 1995 and 2003 there were “no significant differences in human activity.” “That’s correct,” he confirmed, noting he had conducted spot checks to be sure. His conclusion remained the same: between 1995 and 2003, there were no observable changes in villages and settlements.

“We have no further questions,” the defence concluded.