JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

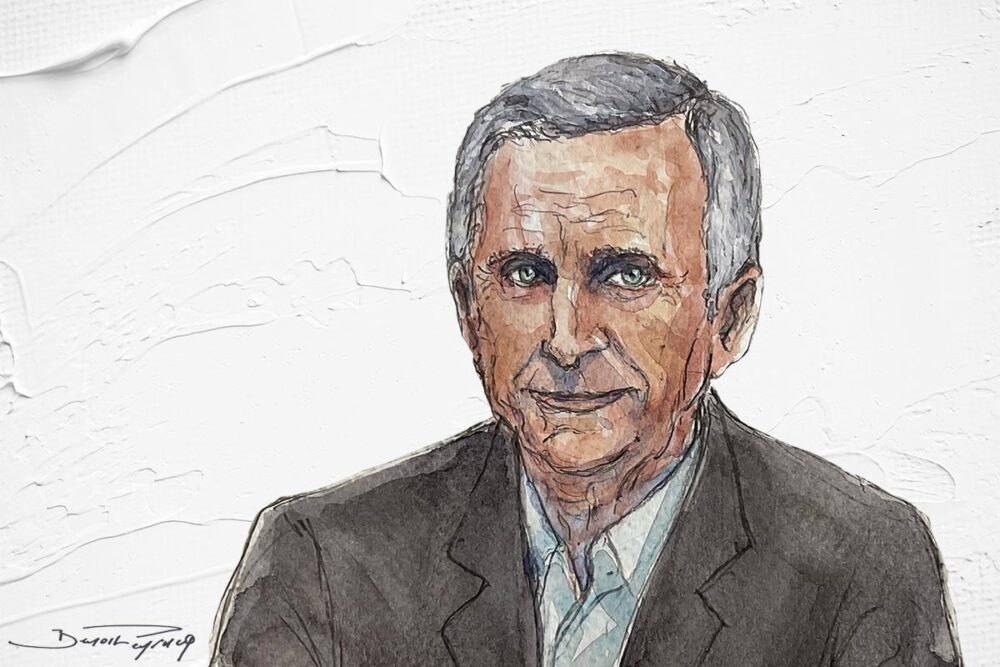

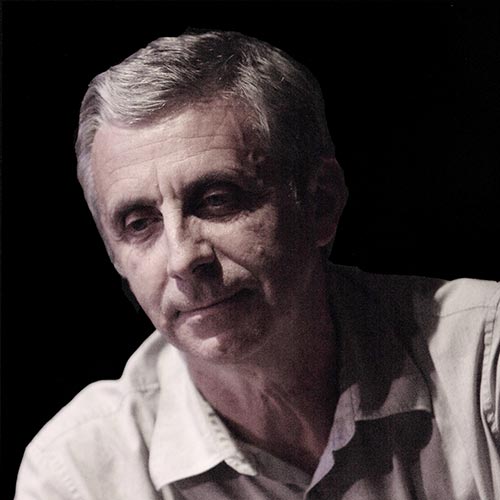

Christian Delage

Historian and film director

JUSTICE INFO: What prompted your interest, as a historian and filmmaker, in the use of images at the Nuremberg trials?

CHRISTIAN DELAGE: I knew that images had been shown at the trial of Nazi dignitaries, but I hadn’t done any documented research on the subject. I began doing so in the early 2000s, visiting the National Archives in Washington DC. This led to my first article, “Images as Evidence: The Experience of the Nuremberg Trials”, which helped me obtain a Fulbright research grant to spend an extended period in the United States. I then investigated how, in the summer of 1945, the Allies gathered a collection of documents, mostly written, to build a case against Nazi leaders on criminal charges of crimes against peace/crimes of aggression, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and conspiracy to commit these crimes. The sheer volume of archives gathered in Europe by the team of Attorney General Robert H. Jackson is all the more impressive when one considers the time special envoys had to gather evidence in support of the charges. It was in this context that Jackson took two unexpected initiatives: presenting images as evidence at the hearing; and filming the trial sessions to create a historical archive.

“The aim was to confront the Nazis with their own crimes and to capture their reactions during screening”

Was this the first time that images had been used in court, and how did this affect the legal proceedings?

In the United States, there had already been civil trials that used photographs and then moving images as evidence. The Allies also believed that images could play a role in confronting Germans who were not in the vicinity of the concentration camps with the crimes committed by the Nazis. During the trial, news footage from the Nazis themselves was shown in the form of a several-hours’ long montage produced by John Ford’s team entitled The Nazi Plan, as well as a few salient images showing persecution of the Jews, plus American and Soviet documentaries on the liberation of the camps.

In order to project these images in the courtroom, the usual layout of a trial had to be modified when the Nuremberg court was redesigned by American architect Dan Kiley. Thejudges were no longer seated in the centre, as the screen was placed there, symbolically giving it the role of a third party. The aim was to confront the Nazis with their own crimes and to capture their reactions during screening by the American prosecution on 29 November 1945 of the film Nazi Concentration Camps, by placing lights above their benches to illuminate their faces.

Who was in charge of filming the trial?

In one of my films, From Hollywood to Nuremberg: John Ford, Samuel Fuller, George Stevens, a letter is read out sent by Ray Kellogg to Ford, who was his right-hand man. He tells him that “it’s the good old army” (the Signal Corps, in charge of communications) that was handling – and mishandling – the preparations for filming. But it was the Field Photographic Branch, the special team led by Ford filming the war from 1942, that was tasked in June 1945 with making a short film presenting the issues at stake in the trial (That Justice Be Done), editing the documentary on the camps, and preparing to film the hearings. Kellogg helped build the projection booth. The operators were instructed to keep the camera locations discreet so as not to disrupt proceedings, a constraint that would later be encountered again during the Eichmann trial [in Israel, in 1961] and the trials of Klaus Barbie and Paul Touvier [in France, in 1987 and 1994]. It should be noted that the Soviets also participated in the filming, in presence of Roman Karmen.

“The 35 mm cameras used were loaded with reels that did not exceed 13 minutes. Therefore, only certain moments were filmed.”

You say that filming of the trial began right from the start, but it seems very little was filmed, since we only have about 30 hours of footage available today. Why so little?

As the filming was not carried out by professionals trained by Ford, the cameramen were inexperienced. The 35 mm cameras used were loaded with reels that did not exceed 13 minutes. And it is not easy to convey the dynamics of confrontation between parties to the trial through images. Therefore, only certain moments were filmed. Unfortunately, sometimes a sentence is cut off in the middle. When my colleague Caroline Moine and I prepared my film “Nuremberg, the Nazis face their crimes”, we benefited from the digital transfer that had just been made by the Holocaust Museum in Washington. But we had to piece together all the rushes in chronological order and add captions. This work took two months, but we were able to create a comprehensive archive of the trial, which we deposited with the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the Holocaust Museum in Washington.

“The international tribunals set up to try crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda were filmed, but with the novelty that there was no longer a director”

Did the legacy of this work influence subsequent trials, first the Eichmann trial, then the more recent international tribunals of the 1990s?

Of all the trials that have been filmed since Nuremberg, the Eichmann trial was the best filmed. The footage was broadcast in a 500-seat theatre near the court, and excerpts were released each week for use by television stations around the world. Eichmann’s lawyer, Robert Servatius, unsuccessfully attempted to oppose the filming, putting forward two arguments: “The fact that the proceedings are being recorded for television and film may lead witnesses to not give their evidence sincerely, firstly because they may feel apprehensive that their televised testimony is being watched outside the courtroom, and secondly because of a desire to impress a global audience”; “Television recordings are likely to lead to a distorted presentation of the hearings, for example by omitting the defence’s arguments”. The judges rejected these arguments, arguing in turn that the measure was relevant and had no negative effect on witnesses or the audience.

As for the international tribunals set up to try crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda [ICTY from 1993, and ICTR from 1994], they were filmed, but with the novelty that there was no longer a director, only a manager employed by the tribunal’s audiovisual department who operated automated cameras.

As for the images presented as evidence, the ICTR had very few at its disposal, as the genocide took place far from the cameras. On the other hand, for the former Yugoslavia, there are many images, in particular those shot by a Serbian paramilitary group. These are currently being analyzed by Ninon Maillard, who heads a research group, ProFil, “La Fabrique du procès filmé” (The Making of a Filmed Trial), and has been investigating for several years the so-called “Scorpions” video, an emblematic video that was the subject of intense debate at the hearings.

In France, the only trial that was properly filmed was that of Paul Touvier, a former Vichy militiaman accused of complicity in crimes against humanity for the execution of seven Jews in retaliation for the assassination of a propagandist. This trial contributed to the debate on responsibility of the French state during the Occupation. It was the last trial to be filmed with camera operators in the courtroom, under the supervision of Guy Saguez, an experienced director who was aware of the historical and memorial issues at stake. Since the Papon trial [in 1997], cameras have been installed in courtrooms and controlled from a studio. In most cases, the filmed recordings are used for external broadcasting of the hearings when the courtroom is not large enough to accommodate everyone who wants to attend.

More recently, in the case of major contemporary trials such as those relating to the attacks of January and November 2015 [terrorist attacks in France], things have been a little different. The civil parties were able to listen to the proceedings remotely, with the filmed recordings being broadcast in rooms reserved for the press and researchers. The societal stakes were very high, as Martine Sin Blima-Barru and I pointed out in the exhibition “Filmer les procès” (Filming Trials).

“This requirement to film is never a priority for judges. It is not part of their culture or their concerns”

However, this requirement to film is never a priority for judges. It is not part of their culture or their concerns, as their primary role is to try the accused. But it is also a generational issue. Young judges and lawyers are better prepared and more informed about the requirements for filming hearings and the importance of video evidence.

The trials that have been filmed constitute a large archive, but access to it appears to be very limited.

For the time being, in France, it is researchers and soon filmmakers – subject to authorization – who can consult these images, because the general public cannot access them for 50 years, but this restriction applies to all archives. However, there is a contradiction between the stakes I have highlighted, i.e. keeping a complete record of a historically significant trial, and standards for the preservation and communication of national archives. Publicizing the proceedings conflicts here with respect for private privacy.

On 4 April 2022, five weeks after the Russian army invaded Ukraine, President Zelensky referred to a “Nuremberg for Ukraine” and said: “The time will come when every Russian will learn the whole truth about their fellow citizens who killed, and make it known to the whole world. We are now in 2022. We have many more tools than those who prosecuted the Nazis after the Second World War”. What new tools is he talking about?

He is essentially talking about visual tools. How were Ukrainians able to convince themselves, in a concrete way, that they were about to be invaded? It was through the first American images from the Maxar satellite, which showed this incredible convoy advancing extremely slowly from Belarus, and which we understood was heading towards Kyiv. The satellite images are also those that Elon Musk allowed the Ukrainians to use.

Then there are the drones. I think everyone now understands that they have several functions. They have a surveillance function: in the trenches, Ukrainians use drones to anticipate the enemy’s movements and operations on the surface. And drones also have a criminal purpose, since they are weapons used on a daily basis, sometimes specifically targeting civilians. A real drone race has taken place in this war.

Finally there are of course mobile phones, which are widely used by citizens. Twenty million Ukrainians use a multifunctional application, DIIA, with which they can carry out administrative procedures, but also alert an authority close to the Ukrainian army command of an enemy soldier’s approach, a bombing, a crime that has just been committed, or the need to send immediate assistance.

On the judicial front, the Ukrainian Attorney General opened investigations very quickly -- in parallel with those of the International Criminal Court -- with the assistance of NGOs such as the Centre for Civil Liberties, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022, and digital investigation platforms such as Bellingcat, Eyewitness and Truepic. These organizations have already worked in other conflict zones, in Syria, Iraq and Chechnya. Bellingcat, in particular, has a wealth of expertise and can react very quickly: its first investigation came immediately after the discovery of massacres in Bucha [near Kyiv], and it was an extremely thorough investigation.

“The probative value of an image can only be established in the context of a court case. Today, images go viral before a trial, whose role is then to put them into perspective and contextualise them.”

In your book Filmer, juger. De la Seconde Guerre mondiale à l’invasion de l’Ukraine (Filming, Judging: From World War II to the Invasion of Ukraine), you talk about an “evidence protocol” that began at the start of the war in Ukraine. Could these images be used as evidence if a major international trial were to be held tomorrow against the Russian invader?

What is very surprising in Ukraine is the speed and quality of the investigative work being done. The difficulty now lies in cross-referencing all these sources so that they are more digestible, easier to store and use when the time comes in a court case. The applications I mentioned make it possible to authenticate the images sent by citizens, to verify their captions – the place, time, people present, nature of the event, etc. – but also to store them permanently and classify them so that they can be used. All this work is being done on several levels, nationally and internationally.

The probative value of an image can only be established in the context of a court case. In Nuremberg and Jerusalem, images of the extreme violence perpetrated by the Nazis had a particularly shocking effect. Today, images go viral before a trial, whose role is then to put them into perspective and contextualise them. This is a major responsibility.

Historian and film director Christian Delage has taught at the University of Paris 8 and Cardozo Law School in New York. His films include Nuremberg, les nazis face à leurs crimes (ARTE, 2006) and 13 Novembre, des vies plus jamais ordinaires (Histoire TV, 2022). He is the author of L’Historien et le film, with Vincent Guigueno, and Filmer, juger. De la Seconde Guerre mondiale à l’invasion de l’Ukraine (Gallimard, 2018 and 2023). He is currently working on the legacy of Nuremberg in building evidence of the crimes Ukraine has been suffering since 2014.

NUREMBERG ON JUSTICE INFO AND RADIO FRANCE INTERNATIONALE

Meet again historian and filmmaker Christian Delage in Clémentine Méténier's investigation for Valérie Nivelon's documentary program “La marche du monde” on Radio France Internationale (RFI): Is the Nuremberg Tribunal still a reference point for Ukraine, Gaza, or the DRC?

Eighty years after the historic trial of senior Nazi officials, how can we draw inspiration from this seminal international court to combat impunity in armed conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, and the DRC? Is a Nuremberg for Ukraine, Gaza, or the DRC possible?

With contributions from William Schabbas, professor of international criminal law and human rights, Thierry Cruvellier, editor-in-chief of the Justice Info website, Rafaëlle Maison, professor of international law, and Reagan Miviri, lawyer at the Congolese Institute for Research on Politics, Governance, and Violence.

Broadcast on Saturday, November 22, on RFI at 3:10 p.m., then available as a podcast (in French).