The allegations under examination are “extremely grave,” said inquiry chair judge Charles Haddon-Cave, dressed in a black jacket, white shirt and dark red tie, at the October 9 opening session. They are threefold, he explained at the Royal Courts of Justice in London, the capital of the United Kingdom (UK): “First, that numerous extra-judicial killings were carried out by British Special Forces in Afghanistan during the period mid-2010 to mid-2013; second, that these were covered up at all levels over the past decade; third, that the five-year inquiry carried out by the Royal Military Police was not fit for purpose.”

During two sessions on October 9-11 and 23-26, opening statements from the lead counsel to the inquiry team, lawyers for the families of Afghan victims, the UK Ministry of Defence and the Royal Military Police resonated in the prestigious Westminster law courts. These first sessions were open.

Sir Haddon Cave stepped down from his position as a British Appeal Court judge to lead the inquiry after being commissioned by the Secretary of State for Defence. The rest of the inquiry team is also composed essentially of jurists. The mandate of the inquiry includes “to investigate into and report on alleged unlawful activity by United Kingdom Special Forces in their conduct of deliberate detention operations (‘DDO’) in Afghanistan during the period mid-2010 to mid-2013”, determine whether previous internal investigations “were timely, rigorous, comprehensive, properly conducted and effective”, and “consider what further lessons can be learned, make recommendations and identify such further action as may be required”.

Speaking on the first day, lead counsel to the inquiry Oliver Glasgow explained that a British Special Forces unit is suspected of having killed nine people “in their beds” in a night raid on February 7, 2011 in Afghanistan’s southern Helmand province. The youngest victim was 14. The family insist that all the deceased were innocent civilians, that no one in the compound was armed, said the lawyer. The Special Forces had claimed they were acting in self-defence, he said. Although not named in the inquiry, the forces in question were the Special Air Service (SAS), an elite unit of the British army that was deployed to Afghanistan from 2010 to 2013.

Executing Afghan males of fighting age

This is one of seven examples Glasgow said he will cite of so-called “deliberate detention operations” (DDOs), intelligence-led raids meant to disrupt Taliban bomb-makers and their supporters. British Special Forces carried out hundreds of these during the three-year period covered by the inquiry. “The central allegation at the heart of this Inquiry is stark,” said Glasgow. “It is that the DDOs were abused by elements within UK Special Forces who carried out a policy of executing Afghan males of fighting age in circumstances where they posed no immediate threat or were hors de combat.”

“There are 14 bereaved core participants from nine different families, who between them lost 33 of their loved ones in seven SAS night raids,” said lawyer Richard Hermer in his October 11 opening statement on behalf of the Afghan victims. Addressing chairman Haddon-Cave, he continued: “You, Sir, are of course looking at many more similar raids and deaths that occurred over the same time period covered by your terms of reference, and the core participant families represent only a partial subset of the families affected by the conduct in the relevant period.” This inquiry comes after BBC Panorama reported in July 2022 that an SAS squadron killed 54 people in suspicious circumstances.

Lawyer Brian Altman, in his October 10 opening statement on behalf of the Ministry of Defence, told the inquiry that “the UK's armed forces rightly hold themselves to the highest possible operational standards” and that “the service justice system is capable of investigating and prosecuting all criminal offences on operations overseas”.

He stressed the difficult context. “At this time, UK Armed Forces, which formed part of ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] in southern Afghanistan, operated in one of the most dangerous and challenging regions of the country. The constant threat to UK Armed Forces, Afghan forces and the civilian population was very real in Afghanistan, as the number of military fatalities and the number of injured personnel, many with life-changing injuries including the loss of limbs, attest.”

NATO and allied troops first went into Afghanistan after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York in 2001, in one of the longest, largest and most challenging joint military operations of all time. The aim was to crush the Taliban, support a democratic Afghan government and help Afghan forces. The UK had the largest deployment of forces after the US. At the peak of the campaign, 137 UK bases and about 9,500 UK troops were stationed in Helmand province alone.

Unlikely prosecutions

Altman also told the inquiry that: “The Ministry of Defence wishes to express, through me, and stress its enduring commitment to this inquiry and its continuing intention to provide its full co-operation.”

Iain Overton, director of accountability NGO Action on Armed Violence, which conducted investigations in parallel with the BBC and lobbied for this inquiry, is not so sure. Getting this inquiry has been “like pulling teeth”, he told Justice Info, as is getting information from the UK Ministry of Defence.

He stresses that the SAS, which he says has almost mythical status in the collective British psyche, is currently not subject to accountability, being directly accountable only to the British Prime Minister and Ministry of Defence (MoD). According to Overton, the “cloak of secrecy” around British Special Forces, notably the SAS, and the MoD’s reluctance to have an independent inquiry make it unlikely there will be any actual prosecutions as a result.

Having been forced into the inquiry, Overton says there was a “real attempt by the MoD to make it a closed one”. While the first sessions have been open, the inquiry’s terms of reference say that “there will be closed hearings and all necessary steps taken to protect sensitive material and the security of witnesses”.

Collective denial?

While Western countries went into Afghanistan with the proclaimed aim of exporting democratic values, Overton thinks their way of operating was often far from that. And the UK is not the only country whose forces in Afghanistan have been accused of serious human rights abuses.

The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) opened a preliminary examination on the situation in Afghanistan as early as 2006. In 2020 it was authorised to conduct a full probe into “crimes alleged to have been committed on the territory of Afghanistan since 1 May 2003”. Former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda evoked possible war crimes and crimes against humanity committed not only by the Taliban and Afghan forces, but also by Western forces and in US secret prisons.

But Bensouda’s successor, current ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan, announced shortly after taking office in 2021 that his office’s Afghanistan probe would not “prioritise” alleged crimes by US troops or its allies in that country, but rather by the Taliban and Islamic State. Nevertheless, the threat of ICC indictments may have helped increase the pressure for national probes into alleged military abuses in Afghanistan. This has not happened in the US, which is not a state party to the ICC. But it may have played a part in Australia, as Donald Rothwell, a professor of international law at the Australian National University in Canberra, told Justice Info in a 2021 interview.

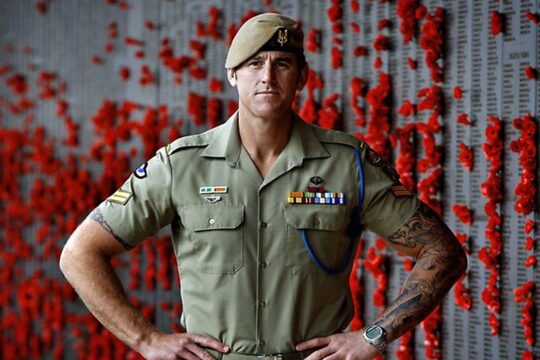

It had taken long, but that year Australia set up a special unit to investigate possible abuses by its forces in Afghanistan. A criminal investigation followed a report that found evidence of serious abuses by members of the Australian Special Forces in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016. The report, known as the Brereton report, was the result of a four-year administrative inquiry commissioned by the military itself. It recommended that 19 individuals be referred for criminal investigation.

Hopes and expectations

So what might come out of the UK inquiry? “What I hope will come out of this inquiry is a recommendation for substantive parliamentary oversight of Special Forces,” says Overton. “I would hope that a civilian casualty recording unit will be set up in the Ministry of Defence, and that there would be an independent Ombudsman with responsibility to ensure that Special Forces are held to the highest level of account.”

Lawyer Hermer, representing the victims, said the Afghan families hoped the inquiry would “end of the wall of silence and the obstruction that has confronted them over the last decade”, and “finally shed light on the conduct of UK Special Forces in Afghanistan and the circumstances of their loved ones' deaths”. “The experience of the Brereton Inquiry in Australia shows that a wall of silence can be very hard to break, but once a single brick is removed, the whole edifice is capable of collapsing,” he continued.

“If your inquiry concludes that there is credible evidence that murders took place and that there was a cover-up, then the bereaved families seek proper accountability for those actions, and proper accountability in those circumstances would require further criminal investigation and prosecution of the implicated individuals. Proper accountability must therefore involve not only the soldiers on the ground, but those who were responsible for their management and their oversight.”

But the probe’s terms of reference say that “it is not part of the Inquiry’s function to determine civil or criminal liability of named individuals or organisations. This should not, however, inhibit the inquiry from reaching findings of fact relevant to its terms of reference”.

Overton says he does not expect prosecutions or reparations – which he says would be a tacit admission of guilt – to come out of the inquiry, although “I hope I am wrong”. “Nobody will be named, so far as I am aware,” he told Justice Info. “There will be no proof of justice being applied.”

No further calendar for the hearings has been published on the official website for the moment. The inquiry is expected to take at least a few more months. Glasgow outlined witnesses who will be called to the hearings in open and closed sessions, starting with expert witnesses. He stressed that the length of the inquiry will depend on the level of cooperation it gets. “If the MoD and the military are true to their word, if they engage with the process collectively and individually, and if they help to uncover the truth, then this work will take far less time than if we have to compel the production of evidence and the attendance of witnesses,” he said.