Claudine*,a retired nurse who was raped by a chaplain when she was young, is one of the pioneers. “In 2019, after the publication of an article about abuse at our lycée, we got together as victims. We were scattered all over France. We organized a meeting, which was very warm and involved a lot of listening. Our group of ten people was received by CIASE in February 2020. I was in Lourdes when the bishops acknowledged the Church had done wrong, and I went to Paris when CIASE issued its report. So I saw the birth of the INIRR, to which I decided to take my case in January 2022.

Michel* was abused at a very young age by a nun. He worked as a psychotherapist and was also one of the pioneers. “When I first heard about the Sauvé Commission [named after the head of CIASE], I said to myself that I was going to testify. I knew straight away that they were interested, because statistically there are fewer abusive women than men. I don’t belong to any associations that demand things of the Church, but I thought that my testimony might seem symbolic and interesting. Reading my anonymous testimony in the CIASE report did something for me; your testimony is immediately recognized as being true. I found the people on the commission very respectful, so I decided to take my case to the CRR, which was just getting started.

François Devaux: “I registered with the INIRR but didn’t go through with it.”

François Devaux is well known to the French public. Along with other victims, he secured the conviction of a scout chaplain and a cardinal from the diocese of Lyon in a high-profile trial. “It was no doubt partly our victims’ association “La parole libérée” that helped get Jean-Marc Sauvé’s CIASE. Throughout the duration of the commission, I was in close contact with the chairman. He asked me to make a speech when the report was published, in which we victims called for the truth to be told. You could say that the two reparation bodies came into being as a result of “De la parole aux actes collective”, which was set up after the CIASE report. We asked for the four Rs: recognition, responsibility, reparation and reform. We asked that the Church recognize the systemic responsibility established by CIASE. And once it had acknowledged this, it had to undertake reparation. We applied media pressure. A few months after the publication of the CIASE report, I registered with the INIRR, but I didn’t go through with it.”

Véronique Garnier was abused by two priests as a child. She is also one of the first wave of victims to come forward. “In 2010, at Palm Sunday Mass, I asked myself what I was doing there. I told myself it was time to come clean with the Church. Forty years after the events, I realized that the opposite of silence is dialogue, with the Church, even if it is complicated and painful. I worked with the French Bishops’ Conference. I was one of the victims welcomed to Lourdes for the first time in 2018. As part of the Faith and Resilience Collective, I worked with CIASE and was interviewed. I was one of the first to submit a file to the INIRR.”

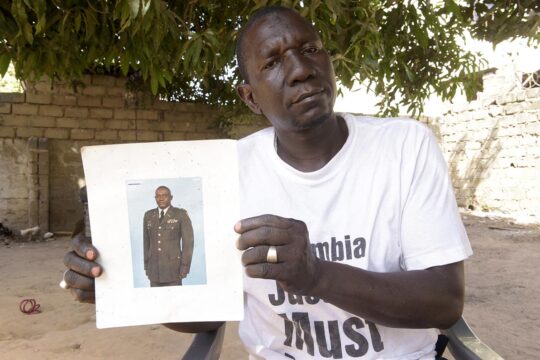

Gilbert: “I wrote to the CRR to see if it was serious. To be honest, I didn’t really believe in it.”

Gilbert* was raped by a priest when he was 12. But it wasn’t until the whole thing exploded publicly in France that he became aware of it. “François Ozon’s film Grâce à Dieu, which I saw in the cinema in 2020, was a trigger. The next day, I went for a routine medical check-up at Nancy hospital. It was the first time I’d spoken to an adult about what had happened to me. The Sauvé report, which was published afterwards and mentioned 330,000 victims, brought out everything I had buried for over 55 years. It was a cataclysm. A year later, I told my children about it. I heard that the French Bishops’ Conference in Lourdes had decided to release money to compensate the victims. What prompted me to write to the CRR on October 21, 2021 was to find out what it was all about and whether it was serious. To be honest, I didn’t really believe it.”

Yolande du Fayet de la Tour, a victim of rape and four years of sexual assault covered up by denial, didn’t believe it at all. “I heard about CIASE like everyone else, but I looked at it from a distance because I didn’t trust it. I said to myself: in any case, this commission is appointed and paid by the Church, so it’s just there to restore its image. It took me a year and a half to decide to go and testify. I did it because it was important for me to speak out for all the people who are silent. It’s as if a pulse of resilience started, without me really deciding. A whole process of remembering and understanding began. The fact of bearing witness and being with others on social networks made me take on this societal and militant role, by creating a collective of victims. On a more individual level, I then decided to apply to the INIRR for recognition and compensation. I filed my claim in September 2023 and have just received compensation (April 2025).

Alain: “I’ve decided not to go to the CRR. As it comes from the Church, it can’t work. We would need a Nuremberg trial, with the Church in the dock as an institution.”

Alain*, who was molested as an altar boy and later became a psychotherapist, thinks that: “As it comes from the Church, it can’t work. It’s totally impossible. These commissions have the merit of existing, except that we see just how flawed they are. I don’t say they are deliberately bad, but flawed. It’s a way of washing dirty laundry in the family. It can’t work. For me to get reparation, there should be a separating third party, in particular a justice system that is independent of Church and State. That’s why I’ve decided not to take my case to the CRR. In my case, it was the system that allowed this kind of abuse to take place, and all the silence that goes with it. [In France] you can’t attack the Church as a legal entity. It’s highly protected. I think it is up to Parliament to legislate to regulate a certain number of religious practices, or maybe even hold a Nuremberg trial with the Catholic Church in the dock as an institution.”

Why don’t most victims seek compensation?

In 2025, it was time for the two commissions to take stock. As of May 6, 2025, only 1,143 people had filed claims with the CRR, 886 claims had been examined and 209 claims were pending. The INIRR has received 1,509 applications since 2022 and provided assistance to 1,235 people. There are a number of reasons why so few people apply to the reparations commissions, according to the victims interviewed by Justice Info.

“I think there’s a kind of collective amnesia,” says Yolande. “Out of 330,000 people, the vast majority don’t realize they are victims. I’ve known I was a victim since CIASE and MeToo Church. Secondly, after recovering from amnesia or denial, many victims tell themselves that if their attacker is dead, there’s nothing they can do, that the statute of limitations has expired, and they don’t think about making a complaint to the institution from which they’ve been estranged for a long time. There’s a link between the institution and the abuse, the systemic aspect, but a lot of people haven’t understood that. I also think that we live in a society where many Catholics have left the Church and no longer have any connection to it.”

“It’s terrible that so few people [are seeking redress],” says Véronique. “The 330,000 people identified by CIASE didn’t come out of nowhere. I think that for some people it’s too difficult because they don’t want to talk about it anymore. For example, a friend of mine was also attacked, but he didn’t contact either CIASE or INIRR, he didn’t want to. I am 64, he’s 69. I think he has probably found some sort of fragile equilibrium, and that he knows very well that if he starts talking, everything in his life is going to go wrong.”

“Let’s not dream: the 330,000 people won’t come out of the shadows. There are all those who have died and all those who don’t even know the commissions exist.”

Alain* also believes that “many people don’t want to stir up the past. They have more or less come to terms with what’s happened in their lives. Among them are those who remain Catholic and don’t want to leave the Church, compromise the future and not have a funeral one day, because you never know what happens after death. It’s a form of denial, of downplaying things, of coping with reality.”

“The commissions are swamped with files," explains Gilbert*. “I think a lot of people have gone to them, but it takes so long. Let's not dream: the 330,000 people won’t come out of the shadows. There are all those who have died and all those who don’t even know that the commissions exist.”

“It’s a strategy on the part of the commissions. These two bodies have been manoeuvring to ensure that the Church pays its bill as cheaply as possible.”

“I think it’s a strategy on the part of the commissions,” says François. “There is a deliberate lack of communication, but also a laborious and exhausting process. If CIASE has received so many testimonies from victims, it’s because it has communicated and put in place tools to receive them. These two reparation bodies communicate very little, publish few if any reports, and express themselves only in response to media pressure. They do not really invite victims to testify, and they do not use the diocesan websites in an effective and relevant way, with a real desire to do so. What’s more, too few people work for them, which creates unbearable waiting times. I think that from the outset, these two bodies have been manoeuvring to ensure that the Church pays its bill as cheaply as possible.”

“The INIRR doesn’t go out of its way to make itself known,” adds Claudine*. “CIASE did a tour of France. The INIRR remains fairly Parisian. It has taken steps to commemorate victims when asked for it, yes. But we’re a long way from everyone coming forward. I don’t think we’ve reached the optimum level in terms of what could be done to get more victims to approach the INIRR. Of course, there are all the counselling centres in churches, but from what I’ve heard, they’re not necessarily people trained to listen.”

Danièle* talks about her experience of a counselling centre. After suffering from traumatic amnesia, her memory of the violence she endured came back to her in flashes in 2020. “I’d see a church and try to get inside to understand what was going on, but every time I couldn’t. At the time, I was feeling suicidal, and I was referred to a church counselling centre in hospital. I was taken into a diocesan office. It was the first time I’d put everything that happened to me into words, and the conversation lasted several hours until the person asked me ‘are you aware that you’ve been raped several times?’ I collapsed, and she was also in tears. She wasn’t clear with me about the next steps, telling me only that the bishop was going to carry out a fact check and report back. She told me about the INIRR without saying that I had the right to contact it. It was a big mistake. When I left that office, I didn’t know where I was, I could have gone under the first car. I waited several months without any news. And it was much later that this person called me back to say: “You need to call the INIRR”. The compensation process began in 2024.

* Pseudonym