Switzerland has long been criticised for slowness on international crimes cases, which were clearly not a priority under former attorney general Michael Lauber. When Stefan Blättler took over that post in 2022, he promised to make international crimes a priority. “As the nation where the Red Cross idea started, we have a special moral obligation to do something,” he told the media in May 2022 after his first 100 days in office.

So, are there any signs of change so far?

“We observed some positive signs,” says Benoit Meystre, legal advisor at Swiss anti-impunity NGO TRIAL International. “In the Algerian and Syrian cases, where for a long time we didn’t know how the investigations were going, the attorney general’s office issued indictments. The fact that the Sonko case went ahead is also positive. These are signs that now the authorities are paying more attention to international crimes than before. But TRIAL International initiated some other cases where developments are long-awaited, so it’s difficult to draw conclusions.”

These include a complaint filed in 2019 for alleged pillaging of rosewood from conflict-affected Casamance, Senegal, and one filed in 2020 against a Swiss company for allegedly being involved in oil pillaging during the Second Libyan civil war. “Apart from the Ousman Sonko case which went to trial and led to a conviction, we don’t know where the other cases are at, which notably limits our possibilities to inform on these matters of public interest,” Meystre told Justice Info.

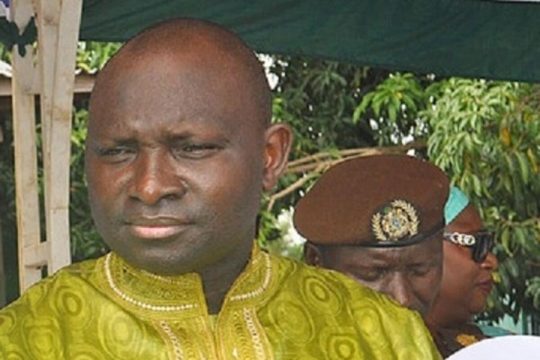

Gambian former interior minister Sonko was convicted in May 2024 for crimes against humanity, and sentenced to 20 years in jail. This is currently on appeal. The only other person convicted of international crimes in Switzerland since 2011, when international crimes cases were transferred from military to civil justice authorities, is former Liberian warlord Alieu Kosiah. A Swiss appeals court confirmed his 20-year jail sentence for war crimes on June 1, 2023.

Meystre points out that the resources of Blättler’s office remain largely insufficient. “Both the federal police and the Office of the Attorney General work with inadequate means, which eventually has an impact on the effectiveness of prosecutions,” he says.

Nezzar dies, Assad keeps fleeing

When Blättler came to office, he inherited two high-profile and politically sensitive war crimes cases: one against former Syrian vice-president Rifaat al-Assad, uncle of deposed president Bashar al-Assad; and one against former Algerian defence minister Khaled Nezzar. The Nezzar case dates back to 2011 and the al-Assad case to 2013. Both men were on Swiss soil when complaints were filed, but – unlike Sonko and Kosiah – were allowed to leave Switzerland, on the understanding that they would return for hearings. But both were protected by their countries and only returned once or twice before arguing that they were too sick to travel. Indictments were not issued until August 2023 in the case of Nezzar and March 2024 in the case of al-Assad. Nezzar died four months after his indictment was issued. He was 86, while al-Assad is now 87.

Nezzar was accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity during his country’s “black decade” in the 1990s. His trial had been set for June 2024, but the case was dismissed following his death.

Al-Assad has also been indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity in connection with the Hama massacre in 1982, which left tens of thousands of mainly civilians dead. Swiss authorities issued an international arrest warrant for him in November 2021 – not unveiled until August 2023 – but this did not stop him fleeing to Syria from France, where he faced a four-year jail sentence for ill-gotten gains. He claims he is too sick to travel to Switzerland for hearings, providing medical certificates from Syrian doctors at the time his nephew Bashar al-Assad was president. But it is widely believed that he fled again from Syria after the Assad regime fell on December 8, 2024.

Court wants to drop Syria case

Victims’ lawyers have always contested the authenticity of al-Assad’s medical certificates. But at the end of November last year, just before the fall of the former Syrian regime, Switzerland’s Federal Criminal Court informed the parties it was considering dropping the case on medical grounds.

“The [Hama] massacre has haunted survivors for 42 years and the indictment finally represented a concrete hope of justice for this trauma,” Geneva-based lawyer Mahault Frei de Clavière told Swiss newspaper Le Matin Dimanche in December 2024.

Frei de Clavière represents a Syrian victim along with two other Swiss lawyers. “We have lost victims along the way,” she told Justice Info. “Given the repression of the Syrian regime, we think there are many victims who did not dare file a criminal complaint. Moreover, after the events in Syria at the end of last year, a number of people contacted us to file a complaint, but for procedural reasons it was too late.”

The court has not yet made a final decision on whether to drop the case. It is possible the final decision could be influenced by pressure from lawyers and the fact that al-Assad is reportedly no longer in Syria. His exact whereabouts are not certain. Media reports suggest he may have fled to Lebanon or Dubai. The issue of credible medical reports for the man who keeps fleeing remains at the heart of the matter.

Switzerland taken to European Court for “denial of justice”

On July 7 this year, lawyers for two victims in the Nezzar case filed a complaint against Switzerland at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) for denial of justice. “We have gone to the European Court of Human Rights for several reasons,” says Geneva-based lawyer Sofia Vegas, who co-represents one of the victims. “The first is the length of the procedure – more than 13 years [investigations plus waiting for trial] – which violates the right to fair justice within due time, independently of Khaled Nezzar’s death. The second reason is that there was denial of justice, because of this violation of the due time principle and lack of access to a judge. The victims have never been able to benefit from a trial before judges to testify on their suffering. And so they have never been able to obtain recognition of what they suffered, nor get reparation.”

Vegas’s client, whom she represents with lawyer Sophie Bobillier, is an Algerian man living in France. He was imprisoned and tortured under the military regime in which Nezzar was defence minister, she told Justice Info. Born in 1949, her client is elderly like other victims, as was the defendant. This, lawyers argue, is another reason why Switzerland should have speeded up the case, rather than slowing it down.

The complaint is based on the European Convention, which lays down the right to a fair trial and encompasses the right to trial in due time. Going to the ECHR is a last resort after an appeal to the Complaints Court of the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. The Complaints Court in March 2025 rejected the victims’ appeal to recognize denial of justice. It ruled that the duration of proceedings was “significant” but still acceptable.

Meystre says TRIAL International strongly supports the complaint to the European court. “Together with the plaintiffs, we believe that the case took far too long, in violation of the victims’ rights,” he says. “The case was opened in 2011, and the indictment was only notified in 2023. The 12 years of investigations, most of which were under the lead of the former prosecutor general, saw several changes of prosecutor in charge of the case, which contributed to delays. In addition, many periods of inactivity during the investigation were identified. Added together, they amount to more than half its total length.”

Vegas says there were also signs of political interference in this case, as was previously alleged by UN Special Rapporteurs, although denied by Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis. This is one of the things lawyers have raised before the ECHR and one of the reasons the case went so slowly, she believes. “There were several exchanges with the Swiss ambassador in Algeria and the Algerian authorities,” she told Justice Info, “and several elements that show this criminal procedure was uncomfortable”.

For example, she says there is a note in the case file from 2016 concerning a meeting between the Swiss ambassador to Algeria and the Office of the Attorney General (OAG). It quotes the ambassador as saying that the Nezzar case is a “time bomb”. And the OAG says that “although it is difficult to know the direct impact this case has had on bilateral relations, we made it known informally that an economic dossier had not advanced because of it”.

Reparations?

Meystre underlines how significant this case would have been if Nezzar had been brought to justice before he died. “No justice-seeking process has been possible in Algeria or elsewhere, in relation to the Black Decade. It would have been very symbolic for some victims, and especially for the plaintiffs who have been engaged in the fight for justice for so long, to at least see one of the main players of such a dark period facing trial,” he told Justice Info.

Vegas says how hard it has been for the victims. “When the Office of the Attorney General finally sent the case to trial, on the insistence of the victims’ lawyers, the victims were finally hoping for a trial hearing before the Federal Criminal Court,” she says. “They were hoping to finally get justice. In the end, it was the opposite that happened, given the death of the accused. It was difficult for them to live with.”

Lawyers are asking the ECHR to order that Switzerland pay reparations of around 10,000 euros to each of the two victims involved. That is the amount that can be asked as reparation for the denial of justice that victims suffered. “Thirteen years is too long,” says Vegas. She thinks there is a good chance the ECHR will recognize this. But such a decision from the European court may also take years.

11 ongoing investigations into international crimes

By Franck Petit, Justice Info

According to information provided by the Swiss Attorney General’s Office (OAG), it was conducting eleven investigations into international criminal law offences at the end of 2024. The OAG did not wish to disclose any further information on the nature of these cases or the human and financial resources allocated to them.

Six of the eleven investigations are listed on the interactive map of the Swiss organisation TRIAL International, concerning alleged crimes committed in the Democratic Republic of Congo (targeting Christoph Huber, a Swiss-South African dual national), in Syria (targeting Rifaat al-Assad), in Bahrain (targeting Ali bin Fadhul al Buainain), in Ukraine (concerning photographer Guillaume Briquet, targeted by a Russian commando), in Libya (against a Swiss-based company suspected of war crimes for looting diesel fuel) and in Gambia (looting of rosewood in Casamance involving a Swiss businessman). In the latter three cases, the suspects identities have not been disclosed.

Two other cases, falling under cantonal jurisdiction (concerning Erwin Sperisen of Guatemala and Yuri Arauski of Belarus) should not be included in the 11 cases handled by the Attorney General’s Office, according to the Swiss NGO specialized in universal jurisdiction trials. Similarly, the cases of Ousman Sonko (Gambia) and Alieu Kosiah (Liberia), which have been closed at first instance, are not expected to be included in this count, according to TRIAL International.