Sciences Po Paris

المقال متوفر باللغة العربية / This article is also available in Arabic on the Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) website.

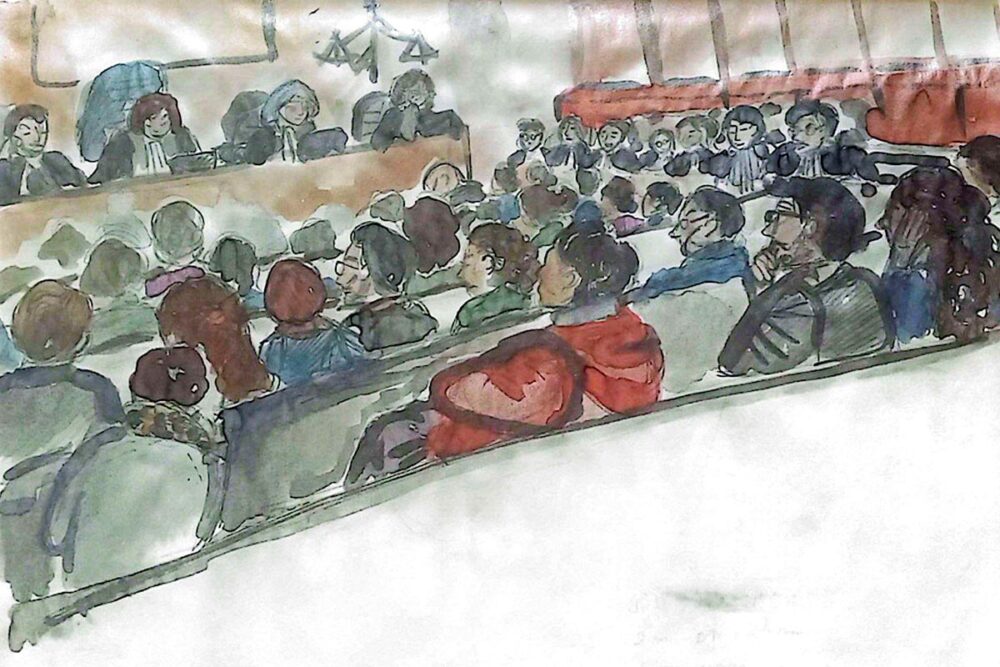

The fourth week of the Lafarge trial, which began on December 1 before the 16th Chamber of the Paris Criminal Court, placed former Syrian employees of the French cement company at centre stage of the case. Proceedings addressed the issue of their safety as well as the responsibility of the French state, “the elephant in the courtroom” of this trial.

On January 16, 2024, the Court of Cassation upheld the indictment of Lafarge, as a legal entity, for complicity in crimes against humanity – a historical first for such charges. However, it also overturned the company’s indictment for “endangering the lives of others”, reasoning that the French labour code did not apply to Syrian employees. The Lafarge case was then “split” into two separate parts by the investigating judges: the first focussing on the financing of terrorist organizations and violation of financial sanctions in Syria - the subject of the ongoing trial - and the second on the charges of crimes against humanity, pointing towards a potential second trial at a later date.

This unprecedented division of the case, based on an artificial separation of facts and charges, has so far led to the issue of Syrian employees’ safety being sidelined throughout the trial. It is still uncertain whether the court will recognize these workers as civil parties when passing its judgment and thus if they will be entitled to compensation. The civil parties have found themselves marginalized, and their legitimacy challenged by the defence. For example Solange Doumic, lawyer for former Lafarge deputy CEO of Operations Christian Hérault, criticized the lawyers of the civil parties for misrepresenting the words of people who had suffered and for overstepping their role as quasi-prosecutors.

Nevertheless, this week, civil parties were able to play a prominent part in the proceedings, confronting the defendants with their moral responsibility towards Syrian employees and addressing the concrete repercussions of their managerial actions. The focus was on safety issues, especially the conditions under which the factory was closed, the degree to which the former managers knew about the terrorist nature of groups receiving payments, and the French authorities’ knowledge and possible involvement in the affair.

“Either I starved to death or I went to work”

The tension in the courtroom was palpable. It was hard to stay indifferent to the testimonies of the former Syrian employees. At the last hearing of the week, on December 5, the finger was clearly pointed at Lafarge for responsibility in endangering Syrian employees and their families. S. J., a former employee, described in tears how his son was kidnapped, and spoke of his deep disillusionment with Lafarge, a company which had benefited from a good reputation at the moment of his recruitment. On November 28, another Syrian witness testifying via videoconference told the court how he was stopped daily by terrorist groups at checkpoints on his way to the factory. At the end of each month, employees were forced once again to put their lives in danger to collect their meagre salaries at a bank in Aleppo, travelling along a road nicknamed “sniper alley.” Lafarge persistently refused to relocate the place of payment despite repeated requests from workers. It only ceded to these demands when one of its workers was killed en route to Aleppo to collect his salary.

These testimonies highlighted the difference in treatment between Syrian employees and expatriates, the latter having been evacuated well before the factory’s closure. “Our lives were much cheaper, much less valued,” said one Syrian employee. “Is it because I am Syrian that I must die?” One of the witnesses also described constant pressure exerted on employees, alleging that the company reminded him that it could recruit other workers in Damascus if he refused to go to the factory. “Either I starved to death or I went to work,” he said. The employees’ resentment remains strong despite the many years that have passed since the events took place. “Now is the time for justice,” one of the former workers exclaimed.

Defence plays the silent card

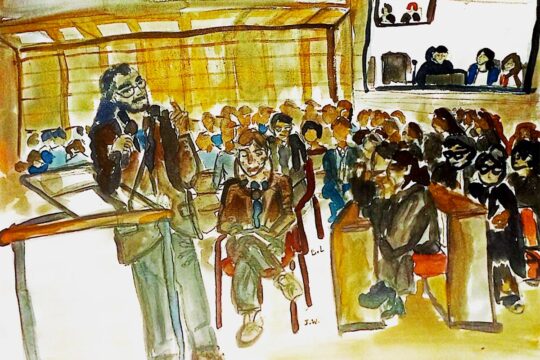

On Tuesday December 2, the hearing focused on the closure of the Jalabiya factory. The defendants’ attitude changed dramatically as soon as the civil parties began questioning them. Their usual strategy—muddying the waters by inundating the audience with details—was replaced by a wall of silence that lasted several hours, with the defendants contesting the civil parties’ legitimacy to participate in the trial.

Frustrated by this unfruitful exchange, the civil parties upped their efforts, but eventually found themselves alone in delivering long monologues. Their lawyers made no secret of their irritation at the defendants’ strategy to drain the hearing of substance.

“You are trying to make yourself understood, but no one understands you,” said one of the civil parties’ lawyers. “Are you lying, or are you incompetent, Mr. Lafont? When you say ‘in my mind, the factory had to be closed,’ were your employees supposed to know what was going on in your head as CEO?” The questions quickly became rhetorical, and the scathing retorts alternately entertained and exasperated the audience. “What a farce!” whispered a journalist.

“Who were you talking about when you mentioned ‘vulgar scoundrels looking to make money’?” one of the civil parties’ lawyers asked Bruno Pescheux, former director of the Syrian subsidiary. “We assume you were referring to the Free Syrian Army. You don’t want to answer? No, because I think I know who the vulgar scoundrels looking to make money are!” Faced with this barrage, the defendants exercised their right to remain silent—with the exception of Jacob Waerness, Ahmad al-Jaloudi, and the legal entity of Lafarge, who replied to the questions.

A surprisingly profitable war

Some of the week’s hearings again focused on money flows. The defendants used company cement sales charts to try and explain the lack of supporting documents for payments to terrorist groups, as well as to employees and intermediaries. The presiding judge, Isabelle Prévost-Desprez, considered it “inexplicable” for a group as meticulous as Lafarge that a large number of supporting documents in the file were absent. Pescheux tried his best to justify the anomalies, saying that “there were certificates of varying quality”. He explained that the unstable situation had disrupted normal working methods and that the amounts fluctuated depending on the context – allowing him to deny accusations of embezzlement. The presiding judge then expressed, with sarcasm, the general sense of bewilderment in the room: “I have never run a multinational company…”

The possible reconstruction of Syria was also discussed in court this week. An email from 2013 cited at the trial indicates that nearly 1.2 million homes were destroyed during the civil war. Profit prospects for Lafarge were considerable and undoubtedly weighed heavily on the decision to keep the plant open for so long under such perilous conditions.

The presiding judge questioned Hérault on this subject. He assured her that at the time, Lafarge’s primary objective was to survive. The company was not continuing its activities in Syria “at any cost”, he said, although he acknowledged it was seeking to remain profitable. “We are not an NGO or a financial institution,” he told the court. Then, the presiding judge replied critically: “So, all these payments were not at any price?” This exchange rang hollow, especially in light of the testimony of the former Syrian manager of the factory warehouse on November 28 : “Keeping the factory open meant maintaining it at any cost. Lafarge was paying to have us killed.”

Involvement of the French State: who are we talking about?

A final sensitive issue was raised at the end of this week: the involvement of the French state, or more specifically the close relationship between Lafarge’s senior executives and members of the French diplomatic corps in Syria.

On September 10, 2014, just as the Islamic State had proclaimed its “caliphate” and the international coalition began its bombing campaign, the director of the Syrian subsidiary, Frédéric Jolibois, met with Guillaume Henry, the French diplomatic adviser in charge of Syrian affairs. In the minutes of their meeting shown in court, Jolibois stated that Lafarge was continuing to pay taxes to the regime but was “not paying anything to the Islamic State” — which turned out to be false.

“So you are lying, sir?” the presiding judge asked Jolibois. He finally admitted that he had “not told the truth”, citing the need to protect the company’s interests. He said he had just been informed that the “problematic payments” had to be stopped and did not know what he should disclose to a representative of the State. “The defendants say they are not lying, that they are simply not telling the truth. But a cat is a cat, not a furry animal,” the presiding judge remarked with a smile.

Eric Chevallier, the ambassador who knew nothing

A lengthy exchange ensued, particularly regarding the role of former French ambassador to Damascus, Eric Chevallier, and his controversial meetings with Christian Hérault. The defence pointed out that the ambassador had initially told investigating judges that he had “no connection” with Lafarge, only to subsequently retract this claim and admit that had met with Hérault on several occasions. Hérault professed that he was “stunned” by this “state lie”, and that they had met four times. But without further evidence, the truth of what was said during these exchanges remains one person’s word against another’s.

Hérault claims he had informed the ambassador as early as December 2013 that “we are giving money to ISIS”. “Are you sure about these dates?” the presiding judge insisted. “We are right in the middle of the period covered by the case!” She then asked: “And that didn’t disturb the ambassador?” “No,” replied Hérault, who maintains that he did not receive any warning from the diplomat. According to him, the ambassador referred to a “transitional phase” in Syria where, in this context, paying “a little” to armed groups seemed acceptable. Referring to the intelligence services’ alleged knowledge of the situation, Pescheux summed up how he felt: “I was confident that France was on my side.”

Although the email exchanges examined since the start of the trial show that the intelligence services were aware of the situation, it is possible that there remained a gap between diplomatic and intelligence information channels. It is still unclear whether the entire state apparatus was fully informed of Lafarge’s payments to ISIS.

Jean-Claude Veillard, Lafarge’s security manager and liaison with the security services—who was ultimately not indicted —will testify on Tuesday this upcoming week. His testimony could shed crucial light on the affair.

As part of the Capstone Course in International Law in Action, Professor Sharon Weill and eleven students at Sciences Po Paris, in partnership with Justice Info, are dedicated to weekly coverage of the Lafarge trial, conducting an ethnography of the proceedings. The members of this student group are Sofia Ackerman, Maria Araos Florez, Toscane Barraqué-Ciucci, Laïa Berthomieu, Emilia Ferrigno, Dominika Kapalova, Garret Lyne, Lou-Anne Magnin, Ines Peignien, Laura Alves Das Neves, and Lydia Jebakumar.