Truth has been on pause, as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has been forced to postpone dozens of meetings and temporarily shutter its 28 regional ‘houses of truth’. Justice has also taken a toll, as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the judicial arm of the system, had to suspend public hearings and court terms on most proceedings.

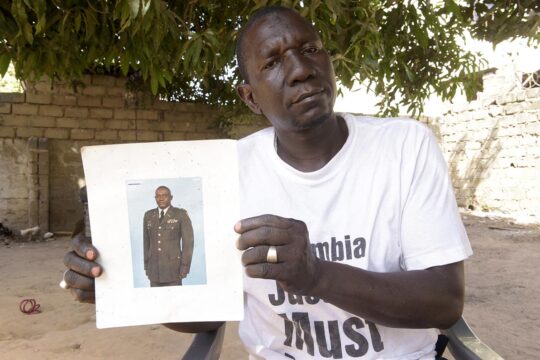

But it’s the victims of Colombia’s 52-year-long armed conflict who are especially feeling the uncertainties brought by Covid-19, as the disease has simultaneously rendered many of them more vulnerable than they were and relegated implementation of the 2016 peace deal in public debate. More importantly, it could end up pushing the reparations they’re expecting further away in time.

“If we stay at home, we might be killed”

“The best way to protect ourselves from the coronavirus is to stay at home, but if we stay at home we might be killed”, Leyner Palacios, a respected Afro-Colombian leader, told Congress during a public hearing on the situation of victims on April 9th, the day in which Colombia remembers its 8,9 million registered victims.

His words highlight the stark conundrum faced by many victims today: the national lockdown designed to flatten the curve of Covid-19 infection is being used by illegal groups to pursue their rackets and regain territorial control in several regions, leaving entire communities more vulnerable to their threats, amid a diminished presence of state institutions.

Palacios’s community of Bojayá is a cautionary tale. The name of this small riverside town in the Pacific region is synonymous with an infamous 2002 massacre, after the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) – who laid down their weapons as a result of the peace deal - launched a cylinder bomb against a church where 119 villagers were seeking refuge. Four years ago, it was also the site where FARC commanders made their first public acknowledgement of responsibility.

Even though security conditions had improved over the past few years, they have declined recently. Confrontations between armed groups already led to the displacement of 74 Embera indigenous families in April, with hundreds more currently constrained. Palacios himself has been targeted, having been forced to leave his hometown in January after receiving death threats and seeing one of his bodyguards murdered in March.

Hundreds of rural communities like Bojayá now fear the arrival of the pandemic to their impoverished regions, which have historically lacked the infrastructure and health services widely available to more affluent urban dwellers. Even though the majority of Colombia’ 8.613 Covid-19 cases as of May 4th were located in major cities and surrounding towns, a remote department like the Amazon has the national highest number of cases per inhabitants, with only eight critical care units to care for patients.

Reparations on hold, in regions ravaged by war

These are also the rural regions where victims have placed higher hopes on the peace deal translating into better living conditions and more opportunities. In fact, the country’s innovative transitional justice system is centred on victims’ rights to truth, justice and reparations, linking any legal benefit for perpetrators to their obligatory acknowledgment of responsibility and to actions redressing those who suffered. One example is Humanicemos, a demining organisation created by a group of former FARC rebels to destroy landmines which, as Justice Info showed, has been mired by bureaucratic hurdles.

This model, in part, mirrors victims’ priorities. Out of their 27,000 proposals sent to the negotiators in the Havana peace talks, victims most frequently emphasised the possibility of rebuilding their lives (34%), even over knowing the truth (16%) or ensuring justice (11%).

To achieve this, the peace deal stresses the importance of stepping up collective forms of redress that allow reaching a higher number of victims. The cornerstone of this approach is a series of regional investment plans seeking to build key infrastructure, improve public services and spearhead economic integration in regions historically ravaged by war. Known as ‘territorial development plans’, they group together the 170 municipalities with highest poverty rates and victim tolls, as well as high institutional weakness and presence of criminal economies, into 16 regional clusters.

The beauty of this territorial approach is that it reflects the needs, desires and projects of communities, ensuring that state programs are not designed in a desk, but really incorporate the ideas of peasants, indigenous and Afro-Colombian inhabitants there

During one year, at the end of Juan Manuel Santos’s presidency, 250,000 rural inhabitants in these regions got together in over 1600 meetings in which they collectively identified their most pressing needs. Then, during his successor Iván Duque’s first year in office, information stemming from these local communities and municipalities was compiled into regional listings of the desired public works.

This ambitious – and often chaotic - participatory process is now in its final stage, as Duque’s government is attempting to translate it into fully-fleshed policy roadmaps establishing investment priorities, institutional responsibilities and funding sources for each of the 16 regional clusters over a 15-year period. Eventually, as Justice Info has told, even FARC commanders’ sanctions should be connected to specific tasks, such as road building.

The first roadmap, in the Catatumbo region bordering Venezuela, was finalised in February. In a highly centralised country where communities’ voices are seldom heard, this has been a welcome change. “The beauty of this territorial approach is that it reflects the needs, desires and projects of communities, ensuring that state programs are not designed in a desk, but really incorporate the ideas of peasants, indigenous and Afro-Colombian inhabitants there,” says Menderson Mosquera, a national representative of victims based in Antioquia.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought these investment plans to a standstill, precisely at the crucial moment in which communities should begin seeing how a three-year process materialises in public works. With government officials unable to travel, 15 roadmaps are yet to be designed and approved by communities and thousands of victims are awaiting one of the most tangible avenues for redress.

FARC’s name change in limbo

One form of symbolic redress many victims anticipate has been similarly postponed, as the political party founded by former FARC rebels was forced to suspend its national congress slated for mid-April. On its agenda was a desperately needed name change. After disarming in mid-2017, their newly-formed party was caught in a heated internal debate on whether to radically distance themselves from the FARC brand or not. In the end, they opted to keep the acronym Colombians knew them by, simply resorting to a slight variation in their longer name – now the Alternative Revolutionary Force of the Commons.

It was a choice seen by most of their victims as a slap in the face and proof of their lack of contrition. A strong feeling further reinforced when a minority group of former commanders announced in August they would abandon the peace deal and return to arms. It was this now fugitive faction, led by former chief negotiator ‘Iván Márquez’, that which had insisted most on preserving their old identity. In the end, this made the Colombian transition quite confusing, with a political party and a rebel group both claiming property of the FARC brand.

The consensus within the party is now to drop their vastly unpopular name. “A good part of us thought it was convenient to leave behind name and acronym, so strongly linked to the war and its circumstances (…) Many things have happened since and we have to get in tune with them”, Rodrigo Londoño, FARC’s military leader and their presidential candidate in the 2018 elections, reflected last year.

At least four names have been touted: New Colombia, Party of the Commons, Force of the Commons and Party of the Rose, in allusion to the red rose they chose as a symbol of their new beginning. Yet they can only do so with a majority vote by its affiliates, something the sanitary crisis doesn’t allow for the time being.

Compensations will take longer to arrive

As concerns over the preparedness of the Colombian health system are compounded by a looming economic depression, some local authorities are already facing decisions of whether to reallocate funds initially destined to reparations towards humanitarian aid for victims who most need it now.

One lawmaker from Duque’s governing party even proposed appropriating the entire budget from peace-related programmes towards Covid-19, forcing the Finance Minister and other top officials to forcefully deny that the government is considering the current crisis as an opportunity to modify a peace deal it doesn’t like but is constitutionally obliged to implement.

In any case, the pandemic will probably delay the individual compensations that the Colombian government began to pay as a result of the landmark 2011 bill that first recognized victims of the armed conflict. However, only 13,8% of the 7,2 million eligible victims have received them so far and it would take 75 years to clear the backlog at the rate it was going before the health crisis, a recent congressional report revealed.

Precisely because this is more than most victims’ lifespans and because monetary reparation has proven so costly and slow, the peace deal insists on a more comprehensive and collective approach to redress that probably has a greater chance of satisfying more victims’ rights. But many of these community-based restorative actions are also behind schedule, not just the territorial development plans. As Justice Info showed, FARC have been reluctant to step up ceremonies in which they acknowledge their responsibility and ask victims for forgiveness.

Even the national psychosocial rehabilitation plan mandated by the peace deal, which seeks to improve access to mental health services and help rebuild trust at community level, is still in a limbo. In charge of it is the Health Ministry, currently tasked with the overwhelming responsibility of coordinating the countrywide medical response to Covid-19.