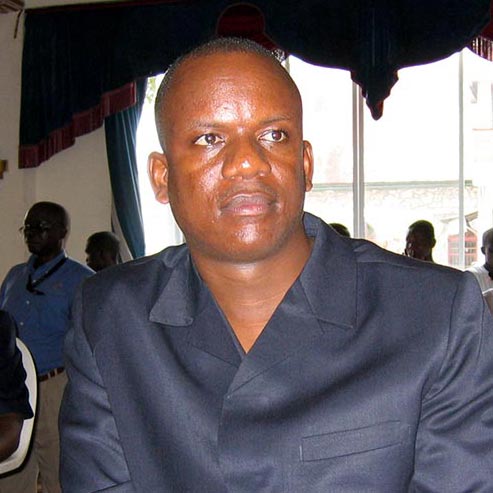

“As a responsible institution, we had no alternative” than to send the archives to Georgia Tech, says Liberia’s former Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) chairman Jerome Verdier, who spoke to Justice Info from the US. As it ended its mandate, the TRC was receiving threats, but he says this was not the only, or indeed main reason why the archives had to be sent elsewhere. The government had no plan, Verdier told Justice Info, for what should happen to these “very, very important” documents and there were financial problems. The lease on the TRC building had run out, the government refused to pay the rent, and it was threatened with eviction. Leaving the archives there could expose them to insecurity and possibly destruction.

So, one night, the Commission “had a bonfire in their backyard where they disposed of the disposable records and the other stuff was sequestered onto a boat at the port and made its way to Savannah, Georgia, then on to us in Atlanta because we were maybe their closest international partner by that time and they just needed a safe archive”, says Michael Best, a professor of international affairs and interactive computing at Georgia Institute of Technology (GIT) in the US who worked with the TRC at the time.

This is a unique case of a truth commission’s archives being expatriated to a foreign university, under an agreement that has now expired.

TRC’s legacy

The TRC worked from 2006 to 2009, collecting some 20,000 statements and hearing direct testimony from over 500 Liberians. It also gathered its own evidence and conducted investigations into a wide variety of crimes committed during the war. The records of this now sit in a warehouse in Georgia, United States.

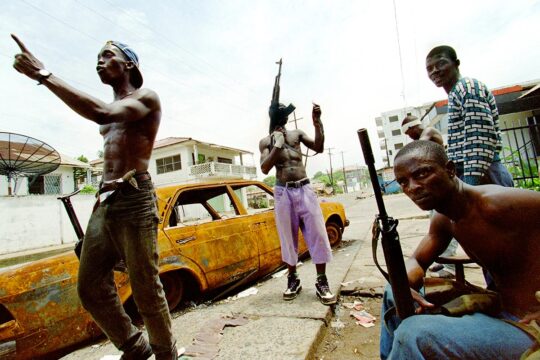

The TRC report, published on July 1, 2009 recommended setting up a war crimes court. This has never happened, and the current government of George Weah remains ambiguous on the issue. Indeed, there have been no prosecutions in Liberia related to the many crimes committed during its two civil wars (1989 to 1997 and 1999 to 2003).

The Commission named a list of alleged perpetrators that it said should be prosecuted for various kinds of gross human rights violations and war crimes. It notably recommended that the country’s president at the time, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, be barred from public office for 30 years for her alleged connections to Charles Taylor, the former president now serving a 50-year jail sentence in the UK for serious crimes committed in neighbouring Sierra Leone.

Liberian government can request them back

Georgia Tech Library’s custody of the archives is governed by an agreement between the GIT, the TRC and the government of Liberia, dating from June 1, 2010, of which Justice Info has obtained a copy. According to Georgia Tech lawyer Shelley Hildebrand, who helped negotiate the accord along with Best, it was signed before the records were shipped.

“TRC and government of Liberia warrant that the transfer of the possession of the records to GIT (…) is authorized and does not violate the laws of Liberia,” says the agreement. It provides that “at all times” ownership and control of the records remains with the TRC and subsequently, after its dissolution, with the government of Liberia. This means the Liberian government can, in theory, ask for them back. But the agreement also says “GIT will relinquish physical custody of the records only when and if a process to securely ship the documents to Liberia (or another location) has been established by the parties and funds to pay for this in place”.

Hildebrand says there have been no requests so far from the Liberian government that they be returned. She told Justice Info that the agreement has officially expired but doesn’t “believe [they] have a duty to send back” the archives. It runs for five years and can be renewed for successive five-year periods “upon the mutual agreement of the parties”. But Best told Justice Info that “at the time of its expiration (and to this date) there has not been an identified interlocutor from the government of Liberia to work with us on a renewal of the agreement”.

“Occasional requests” for access

According to the agreement, “GIT agrees that it will not distribute to the general public or disclose to a third party any records that have been designated as confidential by the TRC” and that “confidential records shall be designated as confidential by an appropriate stamp or legend”. An Annex contains a list of people allowed full access, including to the confidential records. They are TRC Commissioners and key people at Georgia Tech, including Best and Hildebrand.

Georgia Tech has received “occasional requests” for access, says Hildebrand. With a spate of recent US and European cases related to the Liberian civil war, interest has increased. She says Georgia Tech has been working with the US Department of Justice to determine under “what terms we’ll allow access for foreign law enforcement agencies”. She says there have, for example, been requests from authorities in Switzerland and the UK, among others.

According to Hildebrand, the TRC was supposed to label the confidential documents but did not, creating “another sticky situation”, but Georgia Tech has “come up with a process to maintain confidentiality”. Statements to the TRC where the witness said they were “willing to testify” can be accessed on request, but those where the witness was “not willing to testify” are kept confidential. Third parties requesting access must give details of the documents they are seeking (time period, faction, individuals concerned) and then come personally to the Georgia Tech warehouse where they may be allowed access to “only five boxes at a time”.

Aaron Weah, a Liberian former advisor to the TRC for the International Center for Transitional Justice who is now conducting PhD research at Ulster University, says he has requested access to documents and a “few others have tried”. “I spoke to the American archivist,” he told Justice Info. “I requested access but it was denied.” His research relates to memorialization in Liberia, for which purposes he was requesting the documents.

Digitization still to be done

The agreement says that “GIT will digitize the records and will provide three digital copies of the records to each of the TRC, the government of Liberia and the Louis Arthur Grimes School of Law” in Monrovia. But Best says that “we still are working towards this goal”.

Asked about the lessons to be learned from this unique case, Best says there are two. “I think that in principle, when the papers are at risk or the country emerging out of conflict doesn’t have the technical or infrastructural capacities to manage the records, we’ve provided a safe and secure environment, we hold the records in an archival quality housing and the records to this day are in surprisingly good shape.” But, he says, “we’ve struggled to do the real work that we wanted to do, which was to organize the papers, to digitize a lot of it, creating a more lasting legacy. And that is the second lesson to him, that the minute a Commission ends and releases its final report, the donor community just walks away.

Archives could play an important role in Liberia

Best says the archives should go back to Liberia one day when the country “has the capacity” to preserve and manage them.

But for Weah, the archives “serve no purpose in Georgia” whereas they could play an important role in Liberia, for journalists, academics and the wider public. He told Justice Info it would be “good to see them in a national museum”, especially video footage “of historical figures giving an account of the war”. This could serve an important educational purpose, he says, in a country which is still struggling to find a common version of its history and where “we have a very young population with kids born after the Accra agreement [2003 peace accord that ended the civil war]”.

“I think the archives should be migrated to Liberia where they belong,” Weah told Justice Info. But would they be safe now? “The current administration is not at all clear on the reconciliation agenda or the legacy of the TRC or how to address it,” he admits, “so it’s hard to say whether they would be safe. We would need some kind of guarantee that they should be kept and protected at all times.” This might take the shape of a law, which would recognize the TRC archive and provide space for it, he says, and the archives should be digitized, “so that if they were burned, you would still have copies”.

TRC chairman Verdier agrees that the archives should be returned one day, and that is why the agreement says Georgia Tech is only a “custodian”. He said the right timing is not yet there, as “the current government has no interest and I don’t think it can be trusted”. But he does believe that one day there will be a more “responsible government”, at which time the archives should go home.