Think of any person to school on the importance of evidence preservation. The head of an investigation unit in any spy agency would certainly be the last person that comes to mind. Well, Gambia's current spy chief appears to be an exception.

Ousman Sowe was a first batch candidate to the Gambia's National Intelligence Agency (NIA), an institution created in 1995 that came to personify fear under the 22-year rule (1994-2017) of autocratic leader Yahya Jammeh, now exiled in Equatorial Guinea. In 1995, as Sowe "humbly" put it with a smile before the lead counsel of Gambia's Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) on January 6, he graduated top of his batch. In his following 14-year career with the Agency-1995 to September 2009- Sowe would progress from being an agent to an analyst, then head of investigations and, later, of external security. He did so while earning himself a colorful double-Masters in diplomacy and security studies.

And yet he appeared not to have known that plastering walls with alleged blood spatters, removing a torture machine and changing the character of buildings at the NIA was evidence tampering.

The "talk true" machine

Under Jammeh, everyone got to know that you can't mess with the NIA. The sheer mention of its name would send chills down one's spine. Testimonies of several witnesses and perpetrators, including General Alagie Martin and a former NIA director Retired Major Lamin Bo Baaji, have established that what was called investigations at the NIA, was more like "beating the truth out of people".

Sowe, however, was unaware of widespread torture taking place at the NIA.

"The "talk true" machine was a machine at the NIA. What was it used for?" asked Essa Faal, the lead counsel of the TRRC.

"It was said to be used in investigations processes," replied Ousman Sowe.

"Mr Sowe, we are listening to every word you utter. We are paying attention to the nuances, even the cadences. We are listening and we can avoid all the back and forth if you just go for the naked truth instead of casting things in a way that will make you far-removed from the issues. This was a machine that was used to torture people, not a machine that was said to be used to torture people. There is a difference between the two and you know it. Tell us what is."

"The torture machine was a machine I heard of."

"Did you see it?"

"I am coming. Yes, I saw it. [chuckles] For many years being in the service I heard about the torture machine. Until 2003, I did not set an eye on the machine."

"For 9 years you did not set an eye on the machine which had acquired legendary status?"

"Yes. I did not see it until I acquired the position of officer commanding investigations. I saw what now I came to know as the "talk true machine"."

Tampering with evidence

In February 2017, a month after the fall of Yahya Jammeh, Ousman Sowe came back to the Agency as director. As early as in his second week in charge, he began renovation of the complex, removing the infamous "talk true" machine, repainting the torture chamber from red to white and renovating several other buildings, specifically their walls. He reportedly left a notorious "bamba dinka" cell ("the crocodile ditch", a small, dark, mosquito-infested cell at the entrance of the NIA) the way it was to "preserve it". Yet he said he didn't feel the need to preserve torture evidence that he characterized as "fear-inspiring". He insisted his conduct was not "tampering of evidence", an act which would constitute an offence under both the TRRC Act and Gambia's criminal code.

"Did you take any step to cover-up the torture that was happening at the NIA?", asked Faal.

"No," replied Sowe.

"When you took over, there was a torture chamber at the NIA. True or false?"

"True."

"Can you describe it?"

"It was a room with an iron bed. The bed was firmly fixed in the room. It can't move."

"Tell us about the colour of the room."

"It was a red colour."

"Signaling danger?"

"Yes."

"It also had shackles?"

"Yes."

"We have heard witnesses who came here to say that when they were being tortured in that torture chamber, they were fasten on an iron table with their hands chained to the bed and beaten mercilessly. From what you have seen in that room, would you say that those witnesses were truthful about their description of what was in that room and what it was used for?"

"Truthful."

"And you knew, when you went into that room, that it was used for torture. What did you do with it?"

"I instructed that the beds be cut off, the shackles be removed and kept, and the room be painted in white."

"By doing that, you were removing all evidence of the torture."

"I didn't see them as evidence of torture."

"How did you know that it was the torture chamber?"

"When I took over, I was on a tour of the complex when I reached that room."

"How did you feel when you saw what you saw?"

"Shocked. Very, very, very shocked."

"Why?"

"Because that was excessive."

"And what made you think that was excessive?"

"Seeing an iron bed with shackles clearly told you [about] torture."

"Yet, you told the Commission that you did not know that was evidence of torture. You knew quite clearly that this was for torture and you removed it because you were going to conceal an instrument of torture."

"No, I was not concealing an instrument of torture."

"You removed an instrument of torture."

"Yes."

"And you painted the torture chamber from what it was to a completely different thing."

"Yes."

"You completely change the character of that room from a torture chamber to a normal office."

"Agreed."

"You concealed the character of that room."

"That was not the motive. My reason was the shock and deep disappointment that such an instrument would be there in the first place. From the context that is now explained, I now understand it was tampering with evidence."

"It was then and it is now," snapped Faal.

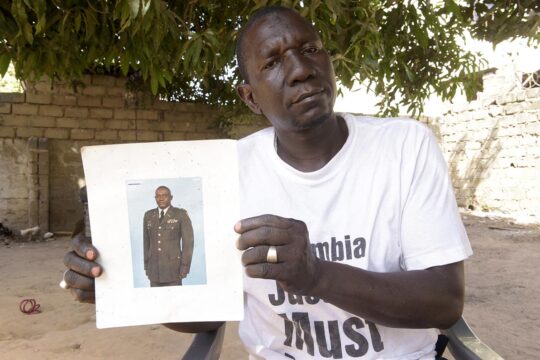

Early warnings

In May 2017, when Sowe was into his renovation project, the Agency's legal adviser Bubacarr Badjie petitioned Gambia's newly-elected president about the issue. Badgie's concerns were that the NIA was not being reformed, that over 200 of its operatives were functional illiterates and that Sowe was destroying evidence that could be vital for future prosecution. "This act [Sowe's renovation of NIA] amounts to tampering with evidence as investigation was being done into death of Solo Sandeng, one of many individuals who had undergone torture there," wrote Badgie in the petition which was copied to the Gambia Bar Association. "[With] the removal of the torture facility at the Investigations Unit, there is risk other such facilities constructed at SIS Safe-houses' will be removed too," he continued, referring to the new name given to the NIA - State Intelligence Services - although that new name was never entered in law. Badgie was redeployed to the police where he was demoted, leading to his eventual resignation. On June 9, 2017, the Agency issued a statement saying information from Badgie, whom they called a "renegade officer", was untrue.

When the TRRC lead counsel confronted Sowe with information that Badgie had advised him not to renovate the NIA, Sowe said: "I don't remember Badgie advising me." But Badgie's petition was widely reported in Gambian newspapers.

In July 2018, the United Nations Human Rights Committee expressed concern over Gambia's "evident" lack of steps to protect "archives of the former National Intelligence Agency (NIA) and other on-site evidence, which may impede the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission in carrying out its mandate". This was also reported in local papers. The UN's statement followed several complaints by the Gambia Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations.

Nevertheless, the renovation work at the Agency continued until the TRRC issued Sowe a letter to stop, in February 2019, after a visit to the headquarters of the NIA.

Denial

When the Commission visited a NIA safe house, several metal hooks were found attached to the walls, much like those described by witnesses, but there were no shackles or metal bed or even handcuffs attached to them. While taking the Commission on tour around the NIA complex, Sowe never mentioned he worked as head of investigations. He did not talk about the torture machine.

"During your years, have you ever witnessed torture in this institution?" asked Faal during the tour of the NIA complex.

"I have never witnessed torture here."

"That would be strange, wouldn't it?"

"It depends on where I am; I worked as an analyst. My job was to stay in the office and analyze and provide reports. So I have never been part of operations or investigations."

"I appreciate that. Of course, analysts crunch the numbers and try to connect the dots and draw conclusions. But the question was more about knowing if torture was happening here and not whether you participated in them. The question is whether you had knowledge that this place had at some stage been used to torture people?"

"I heard about it."

"Did you have knowledge?"

"I have heard about it but I have never seen it or participated in it."

In his testimony before the TRRC, Sowe admitted being involved in the 2009 arrest of Lamin Karbou, an anti-narcotic officer, but he denied any part in Karbou's 14-day torture. He also denied involvement into the torture of Basuru Barrow, another victim of the NIA who implicated Sowe in his torture at the Agency's complex in 2000.

The missing detention register

Several weeks of public hearings before the TRRC uncovered that of 571 known detentions recorded at the Agency, 295 were illegal and no adequate information was available to determine the legality of the remaining 276. This adds to several cases of torture and illegal detentions in at least 8 other known facilities the Agency called "safe houses", across the country. The detention registers which helped the Commission to establish this data was handed to them by Sowe. However, the year of 2004 - which was the time when Sowe served as head of investigations at the NIA - did not appear in the files, suggesting the Agency was not recording detentions at that time or that the file was missing.

"What you gave us did not include 2004," asked Faal.

"It could be."

"Why did it disappear?"

"I do not think it disappeared. I think we gave you what we could find."

"But didn't you find it convenient that the book that would have sought the illegal detention under your watch are the ones to disappear?"

"Well, I don't find that convenient."

"Isn't that consistent with the theory of concealment?"

"If it was hidden, I am not aware of it."

Sowe also faced allegations that he burnt some documents from the office of Louis Gomez, a former deputy director general of the NIA who passed away while in prison, standing trial for the 2016 alleged murder of opposition activist Ebrima Solo Sandeng.

"Did you burn any documents?"

"No," denied Sowe, wearing a wry smile.

There was one issue that Sowe approached with a clenched fist: the rendition of José Américo Bubo Na Tchuto, a Navy admiral of Guinea-Bissau implicated in drug trafficking, to Angola. (Tchuto was later jailed in the U.S. on drug-related offences.) Sowe denied knowledge of the case until Faal informed him that they have documentary proof to show his involvement. Then Sowe backed off.

"I know we were in discussion [with Angola]", he admitted.

"Now you know, and before you denied any knowledge of it."

"Now, I am recollecting. In the Gambia, we did receive a delegation around the subject."

"No, you received a delegation on the subject. You are trivializing it."

"…If you allow me, the reflections are coming back."

"You were involved in those negotiations in both Angola and Banjul," said Faal.

And Sowe eventually conceded.