Talking about human rights in the business world feels “dissonant”, according to François Zimeray. The lawyer, who advises several companies on their human rights obligations, thinks these issues are “still too often perceived by management as a matter of ethics or reputation” rather than a real legal risk for the company and its executives. The most exposed companies—those located in “hostile” areas or operating in sectors such as arms and surveillance—are certainly watching the Lafarge case, “each in their own way,” continues the criminal lawyer. But he does not feel it has brought about a change in “general attitude”. “Too few companies are actually integrating human rights risks into their strategy and giving themselves the means to deal with them,” he says. This inertia is all the more striking given that the risk is no longer theoretical.

Lafarge is on trial in the Paris Criminal Court until December 19 for financing terrorist groups in Syria. The company is accused of paying nearly €5 million between 2013 and 2014 to Islamic State, Jabhat al-Nosra, and Ahrar al-Sham to maintain production at its cement plant as the already war-ravaged region fell under the control of jihadists. As well as the company, eight individuals are also on trial, including former Lafarge CEO Bruno Lafont and former deputy CEO Christian Hérault.

But the most serious charges against the French cement manufacturer remain under investigation. Lafarge, which has since merged with Swiss group Holcim, is also under investigation for complicity in crimes against humanity, a decision that was finalized in 2024. That ruling is unprecedented. Never before has a company been prosecuted as a legal entity for such acts, either in France or in any other national or international court. This is an area that falls outside the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, which can only try individuals.

“Extremely limited” awareness

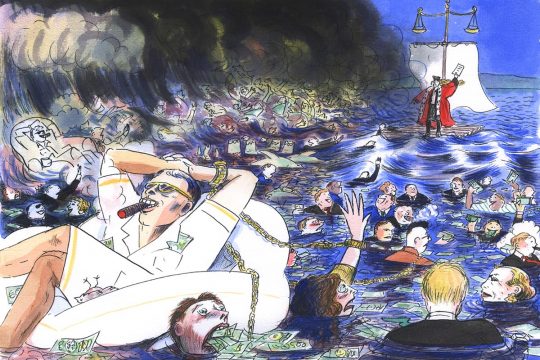

The decision sounds like a warning to the biggest companies operating in areas where international crimes are committed. For the first time, it highlights a risk that has been largely ignored until now, as companies can be accused of contributing either directly or indirectly to such crimes. And there is another thing for these operators to note: in September 2021, the Court of Cassation ruled that a company did not need to share the criminal intent of the principal perpetrator to be deemed an “accomplice”, and that desire to preserve its activities did not exempt it from criminal liability.

But in reality, awareness is “extremely limited”, says Gérald Pachoud, who helped draft the United Nations Guiding Principles—the first global norm addressing the risks of negative business impacts on human rights. As an illustration, he cites the “instinctive reaction” of executives and their legal departments who, when faced with such accusations, remain on the “defensive”. “They tell themselves that they are doing business, and therefore cannot be accomplices to international crimes or have these negative impacts on populations.”

Pachoud, who is also founder of a consulting firm specialized in corporate responsibility, thinks some firms are now examining these risks “much more seriously”. But the fact that management can’t imagine itself to be associated with such “extreme cases” shows a certain “blindness”, he says. He thinks this stems from lack of knowledge and expertise in international criminal and humanitarian law among “corporate people”. This is despite the fact that the “few cases” already known—including the major trial currently underway in Sweden against two former senior executives of Lundin Oil—should be a “wake-up call”.

For Lafarge is no longer an isolated case. In its wake, there have been many more complaints for similar acts filed in France. They target TotalEnergies, Dassault Aviation, Thalès, MBDA France, the Castel group, and BNP Paribas. The French National Anti-Terrorism Prosecutor’s Office (PNAT) has confirmed to Justice Info that around ten investigations and judicial inquiries are currently open against French companies, all relating to human rights violations and complicity in international crimes.

“Very abstract” risk assessment methodologies

These proceedings are also causing concern among financial institutions. According to several sources interviewed, some banks are suspending or reviewing their financing when a company is the subject of a complaint, pending clarification on the legal consequences.

However, it seems that neither the Lafarge case nor the numerous complaints filed in its wake have really changed the way economic actors perceive and understand their responsibility. This is certainly the opinion of the various observers Justice Info interviewed, as none of the multinationals contacted wished to respond. Thalès stated that it did not wish to comment “on this type of subject”.

So it is difficult to say whether companies have stepped up their due diligence or whether they are effectively integrating the need to protect human rights into their operational practices -- beyond charters and commitments posted on their websites.

When the situation requires, as in the Lafarge affair, companies may set up committees and audits designed to identify risks and ensure follow-up. But the methodologies for assessing these risks remain “very abstract”, according to Cannelle Lavite of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), who has sometimes had the opportunity to consult them in the context of proceedings initiated by her NGO.

What she observes is that they are more mechanisms aimed at protecting the company from legal and reputational risk than a genuine due diligence process to identify, prevent, and avoid the risk of human rights violations.

Incompatible objectives

This distinction is not always clear to companies, “which sometimes want us to forget that they have enormous financial and operational resources enabling them to mobilize a host of experts”, the lawyer continues.

As an example, Lavite cites informal exchanges with people in the arms sector. She says legal officials in “fairly senior positions” have confided in her about their difficulties making themselves heard internally, acknowledged the limitations of these compliance mechanisms and the need to recruit people specifically trained in human rights. But such specialists are considered “rare”, she reports, because they are also required to propose solutions that are “adapted to the corporate environment” and its “profit and commercial objectives”. If they are finally recruited, their recommendations are not incorporated into the company’s strategic plans if deemed incompatible with these objectives.

This is where the real paradigm lies, says the lawyer. Companies must identify the risks of human rights violations, but they will not be able to do so “until they accept that this is part of their business model” or that “respecting human rights may mean reducing their profit margin while they check their entire value chain”.

“That’s how things work over there!”

Are companies really unaware of the risks, or do they simply prefer to ignore them? Lucie, who did not want to reveal her real identity, is a former analyst. She worked for several months for French economic intelligence agency ADIT, a discreet agency with sometimes opaque practices. It is partly composed, according to Lucie, of former members of the French foreign ministry and ex-agents of the General Directorate for External Security (DGSE), the French intelligence service. ADIT offers services mainly in consulting and risk analysis, but more broadly in the fields of security and economic intelligence. It also offers support to French companies operating internationally, and participated in the first French delegation to Syria after the fall of Bashar al-Assad, at the initiative of MEDEF, the French employers’ union.

Within the agency, Lucie was in charge of risk analysis for companies “that needed to ensure compliance” – bringing the company into line with rules and ethics – in a region of the world she describes as sensitive and where “the risks are extremely present”. Her job was to verify the identity of local partners working with these groups, including small-scale service providers like meal suppliers, and also analyse their “networks”. “Who are they? Do they have links to armed groups, militias, politicians? Are they subject to international sanctions? What is their reputation, including in terms of human rights violations or corruption?” she explains.

Lucie says such investigations are generally conducted using open sources. But they can also draw on local contacts mobilized by ADIT. “These may be people who have other jobs but are paid by the agency on an ad hoc basis for their information, or people who have made it their business,” she continues. “They interview people on the ground, consult archives, and sometimes take photos.”

“In most cases,” Lucie recalls, “these analyses identify legal or reputational risks. But that’s where the analyst’s work ends, as they don’t know what companies do with this information. “From what my managers have told me, some companies may consider that it is better to cooperate locally, despite the risk, given the security or political balance, often both. Basically, it’s the idea that ‘that's how things work over there!’.”

A network of information sources

“It is often the case that such analyses are not followed up,” confirms Zimeray. But the lawyer thinks these analyses apply overly standardized methodologies that do not always allow companies to properly understand their criminal liability—insofar as the “risk”, which is currently “poorly estimated and mapped”, also depends on “the geopolitical situation, the network of NGOs in the area concerned, and evaluation of the tolerance threshold of local populations”.

Lucie says analyses vary in depth depending on the company’s request. Those that truly incorporate international criminal law and humanitarian law remain in the minority, notes Pachoud. But Lucie says large multinationals often have a fairly dense network of information sources. In addition to consulting firms and economic intelligence agencies, she cites possible exchanges between local company managers and diplomatic or intelligence services. “In some countries, French firms meet with embassy representatives every week,” she points out. Added to this are internal legal departments, risk or security teams, sometimes based in the field, as well as human rights officers—those “rare profiles” that have been integrated into organizational charts in recent years.

This raises the question: how do these companies actually decide between what is identified as a risk and what they are willing to accept to preserve their activities?

Taking risks rather than losses

In France, large companies are already demonstrating their commitment to human rights as part of implementing the duty of care law, says Pachoud. “But because of their lack of expertise, they separate the issue of respect for human rights from that of respect for humanitarian law or, worse, international criminal law.” This leads them, he believes, to “poor analysis”. “Rather than assessing the risk, management and legal departments will first look for reasons why their responsibility would not apply. That’s how they analyse their environment,” he says.

This ambivalence is also evident in a recent report by the Club des jurists, a liberal French think tank, on corporate criminal liability in the area of human rights. While acknowledging the increase in prosecutions and the rise in criminal risk, the report particularly recommends, broadening “economic diplomacy missions” in France and Europe and sharing information on potential “threats” with companies, including those related to human rights violations “in a competitive context”.

“Economic actors need legal certainty,” stresses Didier Rebut, author of the report and professor of law at Paris-Panthéon-Assas University. He says companies are “alerted” but “don’t know how to manage [the risk], because they are facing a risk that is still poorly defined, something “they didn't see coming”. The professor thinks they need “a diplomatic interlocutor” capable of both clarifying red lines and providing them with operational advice on what to do and what not to do. Admittedly, the largest companies have the economic means to cope, Rebut concedes, “but perhaps not small and medium-sized companies”. “I am not saying that we have the right to do anything just because diplomats say it is OK,” he continues. “But they can help make decisions.”

Gaza, a turning point

However, as the Lafarge case shows, this type of approach is not always enough to limit exposure to criminal proceedings or protect human rights on the ground, especially since turning a blind eye is sometimes “deliberate”, according to Pachoud. Companies may consider known cases to be exceptions – which he says “is not untrue” -- and that, if a risk is clearly identified, “they are unlikely to get caught”. This is ashort-sighted calculation, he warns. “Lafarge, Lundin, and other cases show that this risk is no longer theoretical,” says Pachoud, “and we must hope that the Lafarge trial will change this attitude. Because even if the chances are slim, you don’t want to be the company that is accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide.”

Zimeray says companies would be even more wrong to continue underestimating this risk, as these are the most serious criminal offences and are not subject to any statute of limitations. But “as long as sanctions remain rare, as long as there is no real equivalent to the measures put in place for corruption or money laundering when it comes to human rights violations, companies will not have sufficient incentive to act,” he concludes.

Pachoud thinks the current situation in Gaza is a turning point in this regard. “We are in such an extreme situation,” he says, that it seems difficult to ignore the risk. “We now have certainty that international crimes are being committed,” he explains, and in this context “any company that contributes, directly or indirectly, to supporting or facilitating these operations would be on the wrong side of the law”. But, he continues, “I am not sure that many companies have extended their due diligence to ensure they are not connected to these situations”. This would require “robust” measures, he says. He is also convinced that we should expect NGOs to initiate litigation, since in these cases they play “a crucial and essential role, as they will investigate where the justice system initially does not.”