"I believe in the ability of cinema, literature and historians to work on our past and reopen chapters on which the transitional justice process has failed because curtailed by politics," says Lotfi Achour, a Tunisian filmmaker living in France. He has just directed a powerful 14-minute film called “Angle Mort” (Blind Spot) that was broadcast in June on Arte.

The public can also see two other recent works with equally evocative titles by artists clearly committed to fighting the pact of silence. They are “Memory”, a play directed by Sabah Bouzouita and Slim Sanhaji shown in Tunis in January; and an adaptation of Death and the Maiden by contemporary Argentine-Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman which is given local resonance by a Tunisian playwright.

There is also an exhibition called “The Transformation of Silence”, continuing until October 14 at a chapel in the Carthage Institute of Higher Commercial Studies (IHEC), in which artists Hela Ammar and Souad Mani express through photos and installations the need not to forget their country’s past.

Shadowy figures

In his film Blind Spot, Achour returns to the tragedy of Kamel Matmati, whose trial before the specialized transitional justice chambers began in May 2018, inaugurating this process in Tunisia. More than four years later, no judgment has been handed down either in this case of enforced disappearance, or in any of the 204 trials for serious human rights violations examined since then by the 13 specialized courts across the country. The story of Matmati remains emblematic: on October 7, 1991, during a big roundup targeting Islamists, this 27-year-old opponent of former President Ben Ali was kidnapped while he was at work. In Blind Spot, he returns to speak to us 30 years later, asking the question his mother asked during a 2016 public hearing and before the Court of First Instance of Gafsa two years later: "Where did you put my son’s body?"

Achour, who is trying his hand at animation for the first time, uses a technique that gives the human silhouettes a ghostly texture and appearance, shadowy and obscured. The film is almost all in black and white, with only the red stain of Matmati's blood when one of his torturers strikes the final blow. "When the trial opened four months after my death, did the judges know I had been murdered?” Matmati asks in the film. “Why did they let my mother scour the prisons for me when I was no longer of this world?”

For Achour, this story shows "one of the big state cover-ups under Ben Ali”. “In cases of assassination by the security forces, Ben Ali was presented with several scenarios, like the prisoner had escaped or had a heart attack. And he chose which big lie would be used,” says the filmmaker. “It’s from this angle that I want to approach a series on the crimes of the dictatorship. Finding the right form is for me as important as the story itself. Each time it’s a matter of finding the form most suited to the material," says the filmmaker.

The return of old demons

These three emotionally charged projects add an artistic and aesthetic dimension. This allows their creators to bring back strong events for the public, whereas the country’s transitional justice process has been gradually submerged by disenchantment, and the emotions expressed on social networks when victims of human rights violations testified on television during the Truth and Dignity Commission hearings have gradually subsided.

Memory keeps spectators on the edge of their seat. The play makes us feel, with fear rising as we watch, all the suffering of a former victim carried away by the madness of revenge. The story is about Kenza and Morthada, a couple of former opposition activists. One night, a doctor visits their home and Kenza thinks she recognizes, in the man's voice, that of her torturer. Kenza decides to take him hostage to extract a confession from the man who tortured and raped her -- to the music of Franz Schubert's Death and the Maiden. Kenza’s drama recalls the story of Islamist opponent Sami Brahem, who, in his testimony before the Truth Commission, told how the psychiatrist of the prison where he was jailed in 1991 subjected them to "experiments" with homosexual tendencies.

"We found in the original text of Death and the Maiden a dose of humanity, which touched us,” Slim Sanhaji, co-director of Memory, told Justice Info. “There are themes that resonate with us and bring us together."

The fabric of remembrance

The Transformation of Silence is also a transitional justice exhibition. Its curator, sociologist and visual arts researcher Marianna Liosi, was awarded a grant from the Memory and Justice programme of the Merian Centre for Advanced Studies in the Maghreb (MECAM) in Tunis. The Transformation of Silence is the result of her research in the first Arab Spring country. Liosi called on two artists, who express themselves through video installations, sculptures and photographs. Sound plays an important role in the exhibition, echoing the voices, claims and frustrations of the post-January 2011 revolution.

"What appealed to me most in the work of Hela Ammar and Souad Mani is that they work, each in their own way, on the long-term history of their country. I believe that art can help to reconstruct, even to restore the fabric of remembrance, "says Liosi.

Mapping a region in turmoil

In her photographic series entitled Tarz (embroidery), lawyer and artist Hela Ammar mixes images of Independence with images of the Revolution, and connects them with embroidery in red silk thread. Tunisia’s two great transitions are thus linked, leading us to reflect on the fragmentation of memory and its necessary reunification, which was the aim of the Organic Law on Transitional Justice covering July 1955 - December 2013.

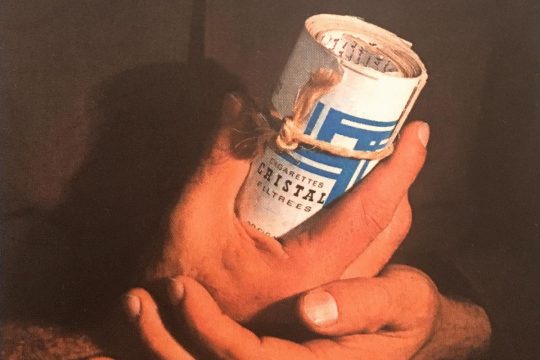

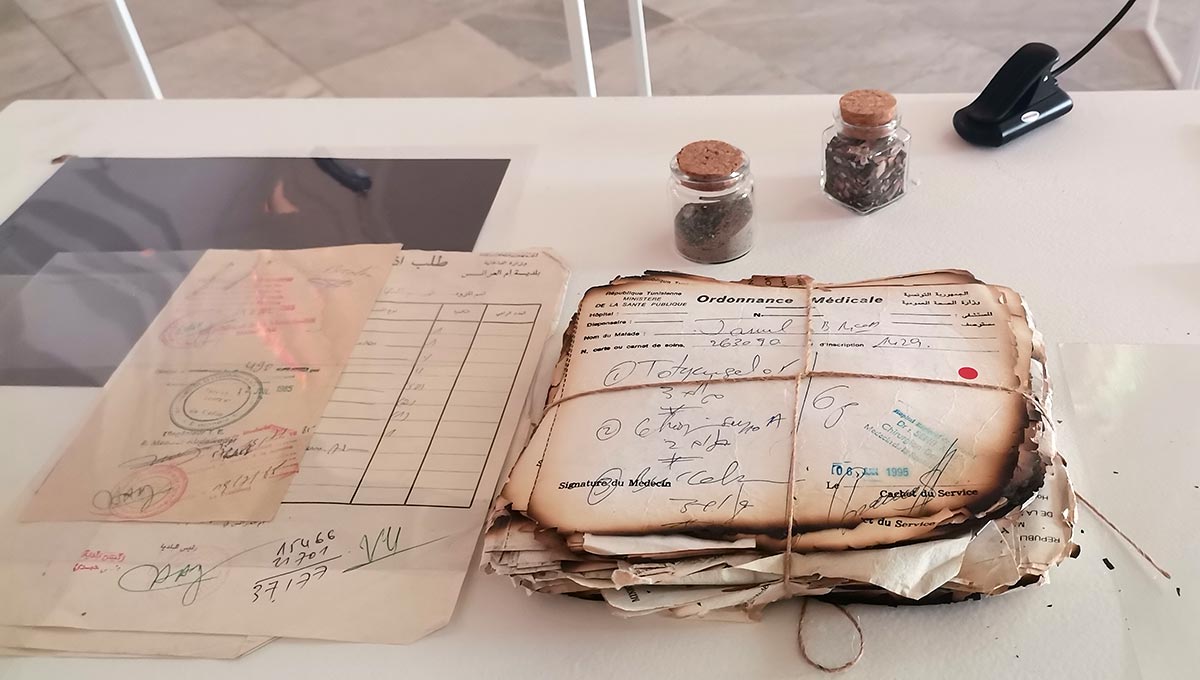

Souad Mani, a teacher at the School of Fine Arts in Gafsa, has long photographed around this part of the country where there was an aborted revolution in 2008, a predecessor to the revolt that broke out two years later in Sidi Bouzid. Gafsa, a land of phosphate mining, has experienced injustice, including that related to air and soil pollution because of mining that benefits the country’s coastal areas. It is the memory of this unfair system that Souad Mani tried to relay in a digital creation and through an installation where she exhibits various objects found abandoned in Gafsa: bills, receipts, medical prescriptions, leaflets of election campaigns from the time of Ben Ali.

"These small documents trace bits of the political and activist past. They become cartographies resurrecting the whole history of the places. Perhaps these raw objects will evolve in a second phase towards a more elaborate creation, so we’ll show the public how this project developed," explains Liosi.

Memory received the Nejiba Hamrouni Award at the last Carthage Theatre Days and continues to tour in Tunisia and abroad. Blind Spot has won many awards internationally but has unfortunately not been selected for the short film section of the next Carthage Film Days.