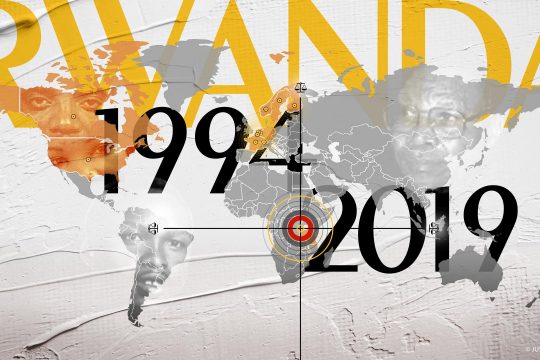

At the opening in April 2018 of Rwanda’s annual commemoration of the genocide of Tutsis in 1994, the executive secretary of the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide, Jean-Damascène Bizimana, expressed concerns. He was not happy with the early release of convicts from the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR) granted by the president of the UN Mechanism in charge of the courts’ residual functions. "It is clear that at this rate, even Colonel Bagosora, who headed the genocide planners, will be released in only three years," said the Rwandan official.

Theodor Meron, the judge who headed the Mechanism at the time, systematically granted conditional release to convicts after they had served two-thirds of their sentence. This had already been done by the ICTY but not the ICTR, which only granted release after the convict had served the full term (in the case of a relatively short sentence) or three-quarters of the sentence. However, the harmonisation of sentencing management between the two UN tribunals served to poison relations between the Rwandan authorities and Judge Meron.

In January 2019, Carmel Agius of Malta succeeded Meron of the United States as head of the Mechanism. Two months later, former Rwandan colonel Théoneste Bagosora, former defence ministry no. 2 at the time of the Rwandan genocide and most notorious of the ICTR defendants, filed his request for early release. Speaking at a debate at the UN Security Council on July 17, 2019, Rwanda's Permanent Representative, Valentine Rugwabiza, said she hoped for changes with the new president of the Mechanism. She reiterated her country's request to be able to give its opinion on every request for early release.

Upon taking office, Judge Agius set the tone by promising to revise the "guideline for assessing requests for pardon, commutation of sentence or early release". The revised text was published in May 2020. It provides, among other innovations, that the President of the Mechanism "may decide to seek or accept the advice of third parties" and that "the granting of early release may be subject to conditions".

Three days of horror in Kigali

On April 1, 2021, after Bagosora had waited two years and just days before the annual genocide commemorations, Judge Agius issued his decision, dashing the applicant's hopes. In his analysis, the judge admitted that Bagosora is eligible for early release: imprisoned since 1996 and sentenced to 35 years, Bagosora has served two-thirds of his sentence as of 2019. But that's not enough, said the judge. Other criteria must be taken into account, among which especially the seriousness of the crimes.

Bagosora was sentenced to life imprisonment by the lower court in 2008, but his sentence was reduced to 35 years on appeal in 2011. The appeal judges overturned several conclusions of the trial chamber. He was held responsible only for failing to prevent the crimes committed by the military and for failing to punish the perpetrators, whereas the trial judges found that he had ordered the crimes. However, the appeals chamber upheld a central finding of the trial judgment -- that Bagosora was the highest military authority in Rwanda between April 6 and 9, 1994, i.e. at the beginning of the genocide. The chamber therefore confirmed his conviction for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Recalling the judgment, Judge Agius noted that during those three days in April 1994, several Rwandan opposition figures were assassinated, Belgian peacekeepers were lynched to death, Tutsi civilians were killed en masse and Tutsi women were raped in various parts of the capital, Kigali. “Even a cursory consideration of the Trial Judgement and Appeal Judgement reflects the enormous gravity of the crimes for which Bagosora was convicted, and my own detailed consideration of these Judgements leaves me appalled at the extremely high gravity of these crimes. There can be no question whatsoever that this factor weighs very strongly against granting early release to Bagosora,” wrote the judge in his decision. Agius also noted that Bagosora had not expressed remorse and that he was trying in his arguments to "minimize his responsibility". Addressing the issue of where he might go in case of release, the judge said Bagosora had not sufficiently demonstrated that the countries in which he proposed to live would accept him. The applicant had indicated that he wanted to join his family in the Netherlands or, failing that, to live in Mali, at his children’s expense.

Seriousness of the crimes

Finally, the judge indicated that he had taken into consideration the opinions of the prosecutor and the Rwandan government. Both opposed the early release of Bagosora, also arguing that the crimes were extremely serious. “For these reasons I hereby deny the application,” wrote the judge at the end of his 19-page decision. With this refusal, Rwanda obtained what it had been demanding for years. The Meron chapter was closed. “The Government of Rwanda welcomes the decision of the President of the [Mechanism] denying the early release of Bagosora Theoneste. (..) We concur with the reasoning and motivation of the decision of President Judge Carmel Agius,” tweeted the Rwandan Ministry of Justice.

But for lawyer Raphaël Constant, who defended Bagosora at trial and on appeal, arguing the seriousness of the crimes does not hold water in this case. "We must remember that Mr. Bagosora was presented by the Prosecutor as the mastermind of the genocide. The trial chamber largely undermined this thesis. The Appeals Chamber only really accepted Mr. Bagosora's guilt as a de facto leader (he demonstrated that he could not be a de jure leader) and not as a direct perpetrator," said the lawyer, who did not represent the convicted person in this early release procedure. "I also recall that during his questioning, Mr. Bagosora indicated that Tutsis had been killed between April and June 1994 in Rwanda simply because they were Tutsis. It seems to me, in this context, that the decision to refuse parole after 23 years in prison, in other words more than two-thirds of the sentence, is highly questionable." For the Martinique lawyer, "in any society governed by the rule of law, Mr. Bagosora would have been released with the simple remission of sentence. This decision shows that we are before a special jurisdiction that applies special rules and not rules of law."

New president, new policy

American lawyer Peter Robinson was not surprised by the shift in the Mechanism presidency’s policy. For two years he has been trying unsuccessfully to secure the early release of another Rwandan convict, former mayor Laurent Semanza. In his view, the decision in the Bagosora case is consistent with the same judge's rejection of Semanza's and other ICTY convicts' requests. “In fact, many paragraphs from the decision were lifted verbatim from those earlier decisions, particularly the discussion about rehabilitation”, in other words indications given by the convict that he has sufficiently changed his ways.

Barbora Hola, co-director of the Centre for international criminal justice at Amsterdam Free University (VU Amsterdam), stressed that up to now this criterion was defined in a rather random way but that, to simplify, “it seemed it was enough if a convict behaved well in prison, participated in language courses or worked in a kitchen brigade, for instance, as a sign of his/her rehabilitation”. Judge Agius, however, has introduced new criteria including the requirement “for a critical reflection by the convict on crimes he/she was convicted of and his/her prospects for reintegration”. While the first policy seemed “not suitable” for international crimes, according to Hola, “demanding a prisoner to critically reflect on his/her past, just because the time passed and they have enough time to do so, without any counselling and trying to elicit such reflection, seems strange”.

“The impact of Bagosora's decision is that there is little hope for those with pending early release applications while Judge Agius remains President of the Mechanism,” concludes Robinson. “He has moved the goalposts on early release so that those who have become eligible during his Presidency are treated differently than those who became eligible when Judge Meron was President.”

Judge Agius remains seized of other applications from ICTR convicts. That of Major Aloys Ntabakuze, who commanded the para-commando battalion within the former Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) and was sentenced to 35 years in jail, was filed on 19 November 2020. But above all there is the application of Hassan Ngeze, ex-owner of the infamous Kangura newspaper that was the standard-bearer of Hutu extremism in the early 1990s. He was sentenced to 35 years and has been imprisoned since 1997. It has been three years since Ngeze applied for his release. In the numerous documents he has sent since last year to the Mechanism and to the whole world in support of his request, the convict keeps claiming that he has repented and that he has dissociated himself from the ideologues of the Tutsi genocide. The former journalist seems to want to show he has adapted to the new requirements of Judge Agius.